Erik Prince's Plan to Privatize the War in Afghanistan

President Trump is meeting with his aides on Friday at Camp David—and some unorthodox ideas are on the table.

Updated August 19 at 11:57 a.m.

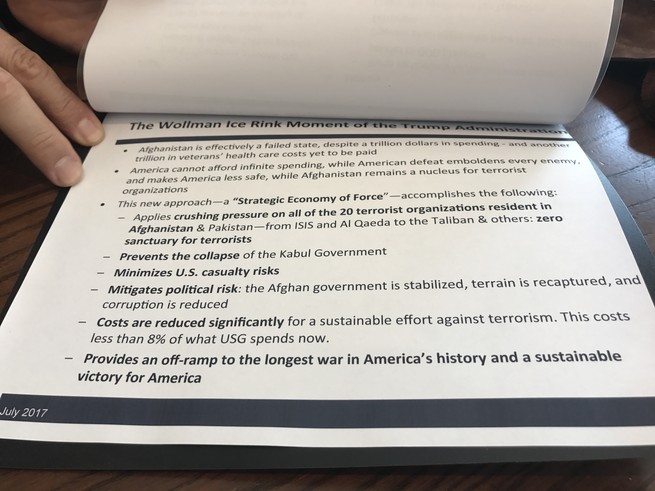

Erik Prince thinks he can turn around the war in Afghanistan, and he’s got a PowerPoint deck to explain the whole thing. The Blackwater founder brought it with him to the Corner Bakery on North Capitol Street in Washington last Thursday, printed out and placed in a presentation binder. He’s been shopping it around D.C. And on Friday, when President Trump huddles with his advisers at Camp David to plot a way forward, it will be in the mix.

The 16-year-old war in Afghanistan has become a central point of conflict in the White House as the administration passes the half-year mark without having settled on a new strategy. Trump has so far rejected the proposals brought to his desk. The troop increases favored by his generals, Defense Secretary James Mattis and National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster, are strongly opposed by his (now-former) chief strategist, Steve Bannon, and the president himself is skeptical of such approaches.

The “America First” ethos on which Trump campaigned is bumping up against the approach of his military brass. But an answer may finally be at hand. Trump and top administration officials will gather at Camp David on Friday to discuss South Asia strategy. Vice President Pence is even cutting his Latin America trip short to join the talks.

But this is not just an argument between warring elements within the administration. Plans to privatize the war proposed by two businessmen with ties to the White House have become a linchpin of the debate. Prince is proposing to send private contractors to Afghanistan instead of U.S. troops, and have the entire operation overseen by a “viceroy.” The billionaire investor Stephen Feinberg has also submitted a proposal using contractors. Both have met with top administration officials on the matter. Their involvement was first reported by The New York Times last month. In recent weeks, their lobbying effort has ramped up, as Trump signals he is nearing a decision. And Trump is said to favor using at least some of Prince and Feinberg’s proposals.

However, a document has circulated within the National Security Council and to Cabinet members this week, according to a senior administration official who reviewed it. It offers notes from meetings ahead of Friday’s showdown, summarizing a plan to convince the president to agree to the “R4+S” escalation plan. The document, this official said, characterizes the surge as the only credible option for Afghanistan, dismissing the other options of withdrawing completely or using contractors or paramilitaries with a minimal U.S. counterterrorism presence. Asked about that characterization of the document, NSC spokesman Michael Anton said it “sounds wrong to me.”

When I met Prince, he was coming from a morning of TV hits. Prince has been campaigning hard in favor of his proposal, as well as shopping it on Capitol Hill and in the White House, where he was headed next.

Prince calls his proposal “A Strategic Economy of Force.” It entails sending 5,500 contractors to Afghanistan to embed with Afghan National Security Forces, and appointing a “viceroy” to oversee the whole endeavor. Prince said some version of the idea had been percolating in his mind since he first went to Afghanistan in 2002; he knew then, he said, that the Pentagon wasn’t going to be able to resolve this. But it wasn’t until the Trump administration that he felt it really had a shot; “There are some phone calls where it’s not even worth wasting the electrons on,” he said when I asked why he hadn’t proposed this idea during the Obama administration. Obama approved a substantial troop increase for Afghanistan in his first term.

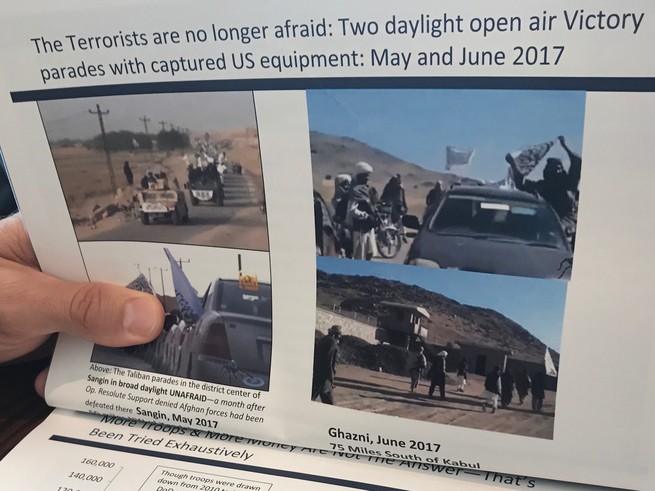

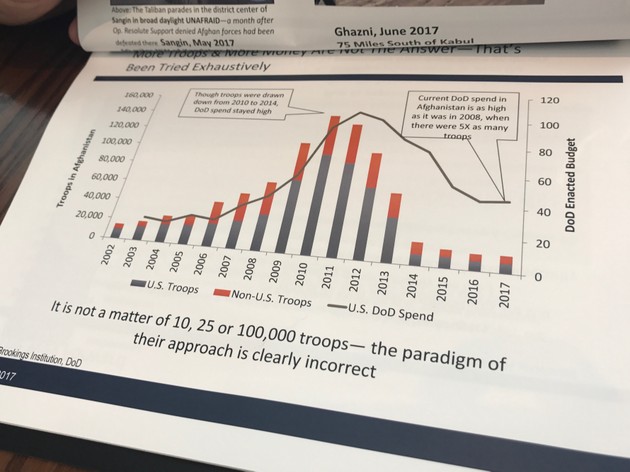

Prince wouldn’t let me keep a copy of the plan, though he showed it to me and walked me through it, and let me take photos of a couple pages—especially the page comparing his idea to Trump’s turnaround of the Wollman Rink in New York. “Make sure to get the Wollman Ice Rink,” Prince said. “Please be sure to use that in the article.”

Under Prince’s plan, the viceroy would be a federal official who reports to the president and is empowered to make decisions about State Department, DoD, and intelligence community functions in-country. Prince was vague about how exactly this would work and which agency would house the viceroy, but compared the job to a “bankruptcy trustee” and said the person would have full hiring and firing authority over U.S. personnel. Prince wants to embed “mentors” into Afghan battalions. These mentors would be contractors from the U.S., Britain, Canada, South Africa—“anybody with a good rugby team,” Prince quipped. Prince also wants a “composite air wing”—a private air force—to make up for deficiencies in the Afghan air capabilities.

Prince said McMaster’s office called him to discuss his ideas after he wrote an op-ed outlining the plan in The Wall Street Journal in May. But McMaster “hates it,” Prince said. Since then, Prince has met with McMaster to discuss the proposal. “He remains committed to more troops and more money,” he said. “We’ll leave it at that.”

The same can be said for the other military brass playing key roles on Afghanistan policy.

“The adults hate it,” said a congressional aide who has seen the plan, referring to McMaster, Mattis, and White House Chief of Staff John Kelly. Mattis acknowledged that his analysis of the problems in Afghanistan is correct, Prince claimed, while disagreeing on his recommendations. A Pentagon spokesperson said “We're not going to discuss the Secretary's private conversations.” On Monday, Mattis confirmed in a press gaggle that the contracting proposals were under consideration.

According to officials familiar with the proposals, Mattis, McMaster, Tillerson, and others in the administration have two main objections to the Prince plan: One is that they believe Prince is downplaying how much it will truly cost, and the other is that they assume allies will ditch the U.S.-led effort once a switch is made to contractors instead of uniformed troops.

It is Bannon and the president’s son-in-law Jared Kushner who have advocated giving Prince and Feinberg’s ideas a hearing. Prince said he had not yet met with the president himself on the issue. “I know he’s seen part of it. I know he liked my op-ed,” Prince said. According to a source familiar with the process, the Prince proposal hasn’t been formally presented to Trump.

Feinberg, on the other hand, has met with Trump, as well as with Kushner. One senior administration official said Feinberg has met more than once with Trump in the Oval Office. Through his investment firm Cerberus Capital, Feinberg controls the huge military contractor Dyncorp. He is also a confidant of Trump and has known him from business circles since before Trump became president. Feinberg was considered for a czar-type position overseeing an intelligence review earlier this year, but the idea was stymied by a vehement backlash from the intelligence community. Feinberg does not have an intelligence background.

Feinberg is proposing ideas similar to Prince’s; Prince said the two were 95 to 98 percent in agreement, though “he wrote his thing, I wrote mine.”

A source close to the situation said Feinberg had been asked to submit a “strategic recommendation” for Afghanistan that is “materially different with respect to the use of independent contractors from the plan Erik Prince proposed.”

Sean McFate, a Georgetown professor and former DynCorp contractor, described Feinberg’s plan for contractors as “more status quo. He wants to take the current mission and just make it bigger.”

But according to one senior administration official, Feinberg is angling to be the “viceroy” described in Prince’s plan.

Prince wouldn’t tell me who he has in mind for the viceroy job, but he confirmed that Feinberg is interested in it. “He’s one of them,” Prince said. “He has a lot of business experience and turning around distressed businesses. So, that’s an option for a guy. But it has to be someone who understands the military and intelligence aspects as well.”

A senior administration official said that the administration has been talking to Feinberg about taking a senior job somewhere in the national-security apparatus, and one option that has recently been discussed is a role in the Afghanistan-Pakistan portfolio.

Feinberg and his aide Lou Bremer, a managing director at Cerberus and former Navy SEAL, have been to the White House recently. Bremer’s Instagram account shows him posing for photos with a litany of Trumpworld figures over the last few months, from Sean Hannity to Rudy Giuliani. One of those photos shows Bremer’s ticket for the presidential reviewing stand at the inaugural parade. Both declined requests for comment.

The pair also have influence at the CIA, whose leadership is said to favor using some elements of Prince and Feinberg’s plans, according to sources. Another source familiar with the discussions said that Pompeo and other CIA leaders are “open to another approach in Afghanistan and realize a change has to be made, because the same thing is not working. They also know it comes with the risks of this town, the type of hyper-politicized town this is. Donald Trump could even cure cancer and people would find ways to criticize him.”

While some members of Congress have dismissed the idea out of hand—Lindsey Graham told The Washington Post “It’s something that would come from a bad soldier of fortune novel”—Prince is finding a degree of support for his plan on the Hill.

Representative Dana Rohrabacher has known Prince for years, since Prince was his intern, and his top aide Paul Behrends is also close with Prince, having worked as a lobbyist and spokesman for Blackwater. Rohrabacher wrote an op-ed last week in The Washington Examiner lauding the proposal.

In an interview, Rohrabacher said that he and Prince had been talking about these ideas for “over a year.”

“Some of us [in Congress] are aggressively pushing” for the plan, Rohrabacher said, adding that Representative Duncan Hunter is also a big fan. But Rohrabacher said the plan was being resisted by “military professionals.”

One of the issues raised by Prince’s plan is that U.S. law prohibits using contractors for combat operations. The workaround is that instead of being categorized under Title 10 of the U.S. code, it will be housed under Title 50, making it subject to the same regulations as intelligence operations. This has sparked concerns about transparency, but appeals to some in the secretive intelligence community.

“I would think the CIA and some other intelligence agencies may have people in the upper echelons who have a better understanding of operations like what Erik is proposing,” Rohrabacher said.

“The biggest drawback is, our military people, our military professionals just hate the idea of not using regular combat units in which there is a really command and control aspect of the mission,” Rohrabacher said.

Critics say Prince’s plan will lead to a moral and legal quagmire, as contractors from around the world fighting in place of U.S. forces present a host of possible problems. What happens if a Canadian, for example, kills an Afghan civilian while fighting as a contractor under the leadership of the American “viceroy”? What if the contractors get in a real bind—does the U.S. send our military in to help them?

“Quality is a problem, accountability is a problem,” said McFate, who wrote a book about modern mercenary warfare. McFate raised the possibility of the Prince fighting force changing allegiances: “It could go into business for itself. It could be bought out by ISIS, China, Russia.”

Over the past 10 years, the industry has become increasingly regulated and professionalized, said Deborah Avant, a Denver University professor who studies mercenaries.

“I would say that most of the industry from 2007 on became sort of increasingly professionalized, normalized according to particular regulatory structures,” she said. “Erik Prince decided to completely go against that.”

Prince sold Blackwater in 2010—Feinberg reportedly considered investing in it—and now heads the Chinese-owned Frontier Services Group, which he says primarily does logistics. He moved to Abu Dhabi in 2010, where he raised an army of Colombian mercenaries for the United Arab Emirates in 2011, but told me he’s now based full-time in Virginia. His sister, Betsy DeVos, is Trump’s education secretary, and Prince was an enthusiastic backer of the president during his campaign. He even met with a Russian national close to the Kremlin in the Seychelles during the transition. The Washington Post reported the meeting was an effort to set up a backchannel between Trump and the Russians. Prince told me he didn’t even know the Russian’s name, and only met with him briefly.

One criticism of the Feinberg and Prince plans is that they are being proposed by people who potentially stand to make a profit off of them.

“I think it will make Erik Prince billions of dollars while he loses the war for us,” a congressional aide who has seen the plan said.

Prince’s argument essentially boils down to: So what?

“If someone is doing that, saving the customer money, is making a profit so bad?” he said. “And let me flip that on its head even more. Before anyone throws that accusation, I think they should interview all the former generals, all the former Pentagon generals, and all the boards they serve on, and all their recommendations … advocating for the Pentagon $50 billion approach to continue on like we’ve been doing for the last 16 years. Which one is it going to be? I’m happy to have that debate.”

Top administration officials, including the president, have said a decision on Afghanistan is coming very soon. Bannon’s faction has sought to slow down the process and give space to ideas like Prince’s. But the extent to which Prince and Feinberg’s proposals are given real consideration could be affected by Bannon’s departure from the White House. Trump fired him on Friday; Bannon did not accompany him to Camp David.

Bannon has been described in news stories as having “ties to” Prince, though Prince said he only met Bannon over the past couple years when he started doing Bannon’s Breitbart radio show to promote his book. Prince has in recent weeks repeatedly promoted his Afghanistan plans in interviews on Breitbart, telling the website just this week that Trump is considering his proposal. Prince also recently gave an interview to the to alt-right reporter Cassandra Fairbanks of Big League Politics, a spinoff site founded by former Breitbart reporters.

Prince said he intends to keep pushing what he calls “the moderate option” in the public discussion. “There’s pullout completely, there’s double down, triple down, after 16 years,” he said. “Even though you might not like the use of contractors, what is there as a better alternative?”