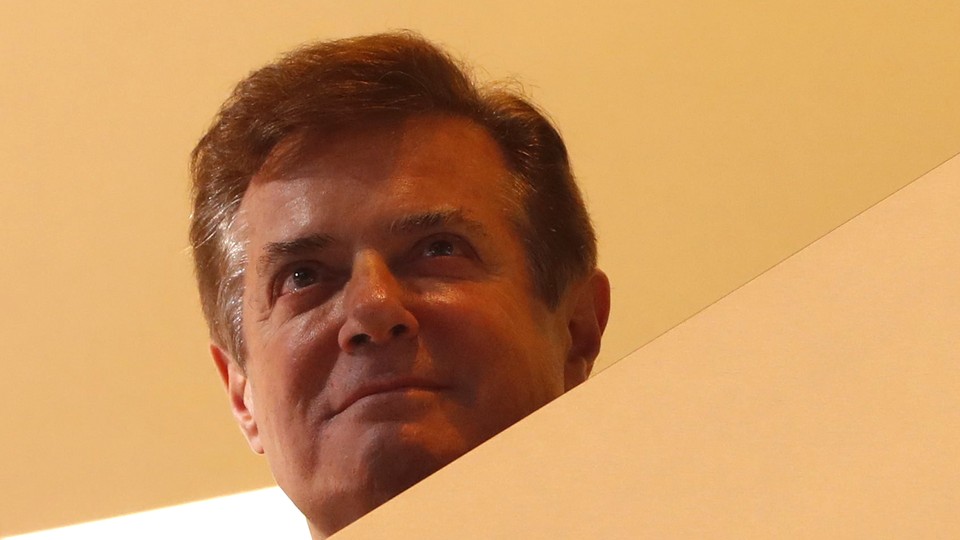

Did Manafort Use Trump to Curry Favor With a Putin Ally?

Emails turned over to investigators detail the former campaign chair's efforts to please an oligarch tied to the Kremlin.

On the evening of April 11, 2016, two weeks after Donald Trump hired the political consultant Paul Manafort to lead his campaign’s efforts to wrangle Republican delegates, Manafort emailed his old lieutenant Konstantin Kilimnik, who had worked for him for a decade in the Ukrainian capital, Kiev.

“I assume you have shown our friends my media coverage, right?” Manafort wrote.

“Absolutely,” Kilimnik responded a few hours later from Kiev. “Every article.”

“How do we use to get whole,” Manafort asks. “Has OVD operation seen?”

According to a source close to Manafort, the initials “OVD” refer to Oleg Vladimirovich Deripaska, a Russian oligarch and one of Russia’s richest men. The source also confirmed that one of the individuals repeatedly mentioned in the email exchange as an intermediary to Deripaska is an aide to the oligarch.

The emails were provided to The Atlantic on condition of anonymity. They are part of a trove of documents turned over by lawyers for Trump’s presidential campaign to investigators looking into the Kremlin’s interference in the 2016 election. A source close to Manafort confirmed their authenticity. Excerpts from these emails were first reported by The Washington Post, but the full text of these exchanges, provided to The Atlantic, shows that Manafort attempted to leverage his leadership role in the Trump campaign to curry favor with a Russian oligarch close to the Russian president, Vladimir Putin. Manafort was deeply in debt, and did not earn a salary from the Trump campaign.

There is no evidence that Deripaska met with Manafort in 2016, or knew about Manafort’s attempts to reach him. Yet the extended correspondence between Manafort and Kilimnik paints a more complete portrait of Manafort’s willingness to trade on his campaign position. Manafort is a high-profile focus of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into the possibility of collusion between Russia and the Trump campaign. FBI agents raided Manafort’s home in July.

Deripaska had been Manafort’s client in various post-Soviet states, but the relationship soured after an investment Manafort managed for Deripaska fell apart. Manafort had represented Deripaska in Georgia and Ukraine, and his firm also represented Deripaska’s commercial interests in Montenegro.

In 2007, Manafort and his partners established a private equity fund that would acquire Ukrainian firms and merge them into larger national entities. Manafort and his partners collected over $7 million in fees for managing this fund from firms controlled by Deripaska, according to a 2014 petition filed in the Cayman Islands, filed by Deripaska’s lawyers.

In 2008, Deripaska transferred $18.9 million to the fund so that it could purchase Black Sea Cable, a Ukrainian telecommunication company, according to the petition. It’s not clear what became of Deripaska’s investment, or if the private-equity fund actually took control of the company. In the Cayman Islands petition, his lawyers alleged the venture had been botched, and requested the “winding down of the partnership.” The petition alleges that when Deripaska asked for an accounting of the investment in 2013, Manafort simply didn’t respond. “It appears that Paul Manafort and [his deputy] Rick Gates have simply disappeared,” the Russian oligarch’s lawyers wrote.

Manafort’s spokesman Jason Maloni has denied that Manafort had done anything wrong. “With respect to the Caymans controversy. Mr. Manafort believes the matter is dormant and will not be pursued further,” he said in a prepared statement. A search of court records shows no filings since 2015.

The emails do not specify how Manafort hoped “to get whole,” but they repeatedly refer to the matter at the heart of the Cayman Islands dispute. It is unclear from the Cayman Islands petition, or from a 2015 filing in Virginia by the liquidators appointed by the Caymans court, whether the collapse of the joint venture left Manafort in debt to Deripaska.

But according to financial records filed in Cyprus in 2015, Manafort was in debt to shell companies connected to pro-Russian interests in Ukraine for some $16 million. Maloni denies that Manafort owed funds to Deripaska, insisting instead that it was Manafort who hoped to collect on debts owed by former clients. “It’s no secret Paul was owed money going back to 2014,” Maloni said in a separate prepared statement. He described the emails as “innocuous.”

Vera Kurochkina, a spokesperson for Deripaska, offered a different account. “The suggestion that Mr. Deripaska owes money to Mr. Manafort is absurd,” she said. “Except for the contents of these emails, Mr. Manafort has never made any such claim. To the contrary, as set out in widely reported court filings, it is Mr. Manafort who has failed to provide any accounting in respect of investments for which he was responsible. Mr. Manafort is the debtor here, not the creditor.”

Despite his apparently precarious financial situation, Manafort went to work for the Trump campaign for free in March 2016. Later that year, he took out $16 million in loans against his New York properties. (The loans are now being investigated by both the Manhattan District Attorney and the New York Attorney General.) In the email exchange that took place two weeks after starting on the campaign, Manafort seemed primarily concerned with the Russian oligarch’s approval for his work with Trump—and asked for confirmation that Deripaska was indeed paying attention.

“Yes, I have been sending everything to Victor, who has been forwarding the coverage directly to OVD,” Kilimnik responded in April, referring again to Deripaska. (“Victor” is a Deripaska aide, the source close to Manafort confirmed.) “Frankly, the coverage has been much better than Trump’s,” Kilimnik wrote. “In any case it will hugely enhance your reputation no matter what happens.”

Kurochkina denied that claim. “There is no evidence that these or any other emails were sent by either Mr. Manafort or Mr. Kilimnik to Mr. Deripaska and they were not,” she said. “Mr. Deripaska had no communications, meetings, briefings, or other interactions with Mr. Manafort during, after, or in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election or for many years prior to that time.”

By the end of April, Manafort was vying for control of the Trump campaign, and was named its chairman on May 19. On July 7, two weeks before Trump accepted the Republican nomination, Manafort again wrote to Kilimnik. He forwarded questions he’d received from a reporter for the English-language Kyiv Post about Black Sea Cable—the sole investment made by the venture. Manafort asked Kilimnik, “Is there any movement on this issue with our friend?” Manafort seemed concerned about whether the journalist’s probing had caught the attention of Deripaska. A source close to Manafort confirmed to me that “our friend” indeed referred to the Russian oligarch. Kilimnik did not respond to requests for comment.

Referring to the journalist from the Kyiv Post, “I would ignore him,” Kilimnik wrote back, responding within minutes to reassure Manafort that it was just “a junior reporter” and nothing to worry about.

In the back-and-forth that followed, Kilimnik suggested that Manafort’s efforts to please Deripaska were succeeding.

“I am carefully optimistic on the issue of our biggest interest,” Kilimnik went on. “Our friend V said there is lately significantly more attention to the campaign in his boss’s mind, and he will be most likely looking for ways to reach out to you pretty soon, understanding all the time sensitivity. I am more than sure that it will be resolved and we will get back to the original relationship with V.’s boss.” The source close to Manafort confirmed that “V” is a reference to Victor, the Deripaska aide.

Manafort had spent several lucrative years working for Deripaska, both as a high-priced consultant-for-hire in former Soviet republics, and as an investor of Deripaska’s money before the collapse of their venture. Manafort jumped on the suggestion that the campaign might offer the opportunity to restore his relationship with Deripaska: “Tell V boss that if he needs private briefings we can accommodate,” he wrote back eight minutes later.

On July 8, the Kyiv Post story on Manafort and Black Sea Cable dropped, outlining in detail how Manafort’s investment on Deripaska’s behalf went “awry.” Kilimnik forwarded the story to Manafort, and added a note to soothe him. “Nothing new here, other than bad and shallow journalism,” he wrote. Manafort, however, seemed more concerned with what Deripaska might think. “You should cover V on this story and make certain that V understands that this is all BS,” Manafort writes, “and that the real facts are the ones we passed along last year.”

On July 29, a week after Trump accepted the Republican nomination, Manafort received another email from Kilimnik, this one with the subject line “Black Caviar.” “I met today with the guy who gave you your biggest black caviar jar several years ago,” Kilimnik wrote. “We spent about 5 hours talking about his story, and I have several important messages from him to you. He asked me to go and brief you on our conversation. I said I have to run it by you first, but in principle I am prepared to do it, provided that he buys me a ticket. It has to do about the future of his country, and is quite interesting. So, if you are not absolutely against the concept, please let me know which dates/places will work, even next week, and I could come and see you.”

Manafort agreed to the cryptic request, responding “Tuesday is best.”

By this point, the correspondence between Manafort and Kilimnik had grown even more veiled. There was no longer mention of Victor or even V; the reference to Deripaska as OVD had fallen out. Yet there are two clues that may hint at the identity of the person whom Kilimnik describes as “the guy who gave you your biggest black caviar jar.” One is a reference to “his country,” apparently not the same as Kilimnik’s, who is from Ukraine. The second is the reference to jars of black caviar. Investigators believe that to be a reference to payments, The Washington Post reported.

On July 31, Kilimnik and Manafort corresponded again to firm up their plans for a dinner meeting in New York on August 2. “I need about two hours,” Kilimnik wrote to Manafort on July 31, “because it is a long caviar story to tell.”

According to The Washington Post, Manafort and Kilimnik met on August 2 at the Grand Havana Club, a Manhattan cigar club. Kilimnik told the Post that the two “discussed ‘unpaid bills’ and ‘current news.’ But he said the sessions were ‘private visits’ that were ‘in no way related to politics or the presidential campaign in the U.S.’” The emails preceding the meeting, however, suggest they had more than bills and news to discuss. Kilimnik had said he needed to relay a “long caviar story” and “several important messages” from his contact about the “future of his country.”

Just days before Kilimnik and Manafort met for cigars and caviar stories in Manhattan, Trump appeared at a campaign rally in Scranton, Pennsylvania. “Wouldn’t it be a great thing if we could get along with Russia?” he said.

Manafort was ousted from the Trump campaign later that month, following a New York Times report that Manafort’s name was listed in a secret ledger of cash payments from the ruling pro-Russian party in Ukraine, and detailing his failed venture with Deripaska. He submitted his resignation on August 19.