There is only one truly serious political problem facing all of us today, and that is climate change. Judging whether or not the human prospect on our planet is worth saving is the fundamental question confronting Americans in particular these coming weeks. Everything else—the fate of the Affordable Care Act, especially in the context of a rampaging pandemic; whether identity politics ought to supersede class solidarity; whether immigration controls should be tightened or loosened; even what to do about that Supreme Court vacancy—comes afterward.

Many of you will have noticed how in the paragraph above, I have been conspicuously borrowing the rhetorical gambit of Albert Camus at the outset of his famous essay The Myth of Sisyphus (substituting political for Camus’s philosophical, and climate change for his suicide, and those various policy debates for his “whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories,” and so forth).

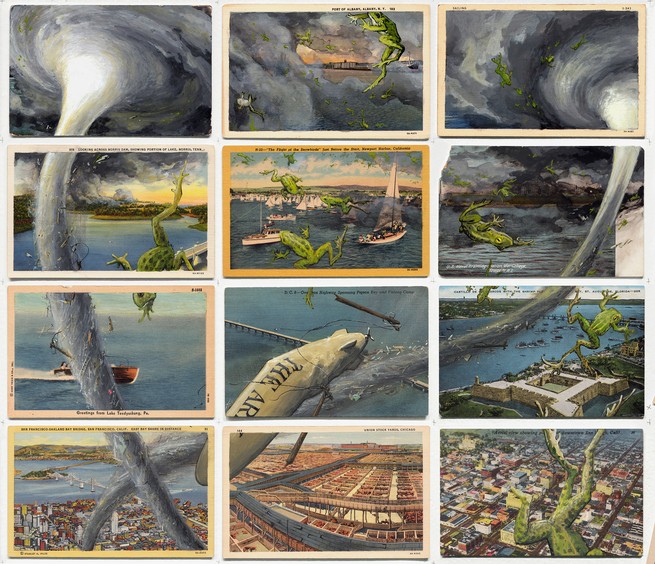

Camus’ essay culminated in the story of Sisyphus, whom the gods had condemned “to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight,” and whom “one must imagine … happy” because “the struggle itself ... is enough to fill a man’s heart.” It seems to me, though, that the challenge of climate change calls forth a different mythological referent: The terrifyingly narrow course that Odysseus and his men were forced to tack between the twin horrors of Scylla and Charybdis, with hideous monster-inhabited crag cliffs to one side and a gargantuan all-swallowing whirlpool to the other.

For Scylla, read Denial; and for Charybdis, read Despair.

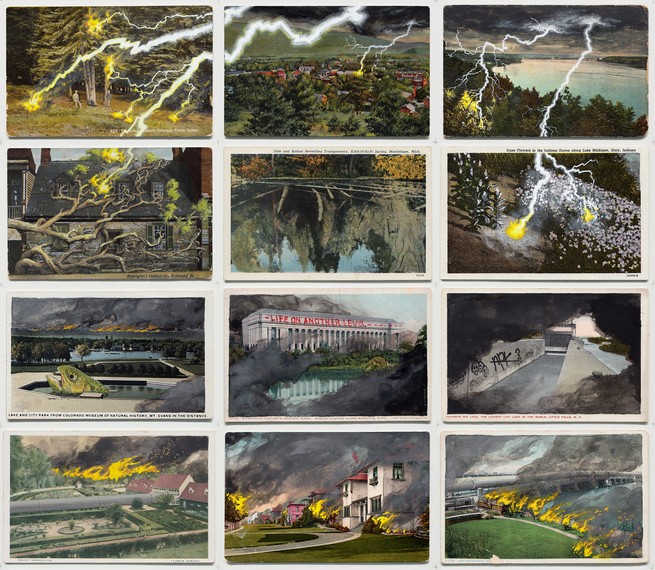

The denialists stubbornly insist that climate change need not be confronted, because, worldwide scientific consensus to the contrary—and notwithstanding all the now-common once-in-a-century storms and conflagrations and droughts and locust swarms and red tides and coral-reef die-offs—climate change simply is not happening, or if it is happening it is not caused by humans, or even if it is so caused it is no big deal, and hence need not be addressed.

Despairers, meanwhile, have simply surrendered, curling in on themselves in stupefied passivity: Climate change need not be confronted or even thought about anymore, because what’s the point? It’s too late, or at any rate, we will never be able to marshal the necessary political resolve—the forces and lure of denial can never be upended. Such thinking leads to a paralysis no less debilitating than, and hardly distinguishable from, denial.

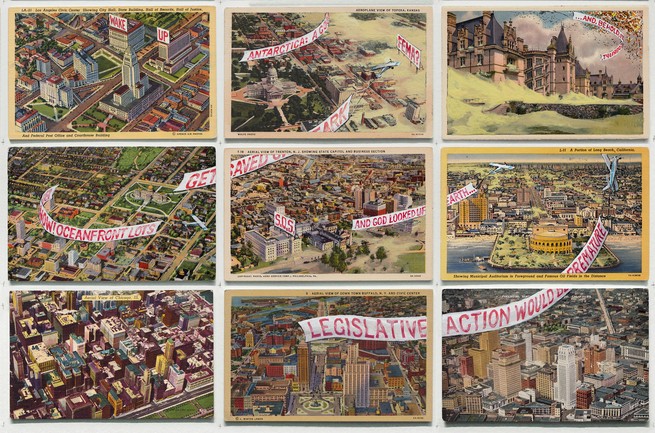

But it is possible, and urgent, to imagine a third possibility in lieu of Denial and Despair, a path forging clean between them: the course of Determined Resolve.

It’s worth remembering, for example, that the entire Manhattan Project in its Los Alamos incarnation, from soup to nuts—from the erection of those barracks and the ingathering of those scientists through the dropping of the first atomic bomb in Hiroshima, as hideous as that outcome proved—took less than three years. And if the prospect of climate disaster indeed calls us to what William James once cast as “the moral equivalent of war,” what would it be like if a president (or, for the time being, just a candidate for the presidency) promised to exercise his considerable authority by bringing together the finest minds in the country (not just scientists but educators and social workers and writers and artists and thinkers and managers as well) to brainstorm better battery technologies; quantum improvements in solar, tidal, and wind technologies and disbursements; desalinization; carbon-capture technologies; meat replacements; massive reforestation; resilient coastline and floodplain projects; and even safe nuclear-power innovations—all on a virtually wartime footing, worthy of the urgencies and streamlined exigencies involved?

What would it be like if incentives were put in place that helped nudge the best young minds in the country toward those kinds of engagement and away from such “bullshit jobs” (in the late, great anthropologist David Graeber’s marvelous coinage) as asset-churning high finance and Silicon Valley unicorn-questing and McKinsey-style consulting?

What would it be like, to consider another example, if we could undertake massive carbon-capture efforts that would end up requiring the deep-burying of vast quantities of solid blocks of limestone-like extrusions? Such technological breakthroughs are well on their way to being perfected. The question now is how to scale them up in an economically feasible manner—a process in which finding ways to bury the millions of tons of resulting blocks will prove key. Wouldn’t it be great if we lived in a country covered over with a massive skein of railway networks leading from every corner of the land to places where there already are cavernous holes in the ground, and workers who once made a decent living taking fossil fuels out of such holes could now be paid good wages to deploy their expertise in helping put carbon slugs back in? And isn’t it great that we do? Might that sort of thinking, the prospect of those sorts of jobs, draw interest from both the denialist and the despairing camps, especially in the context of this election, with such sorts of resolutely determined visions custom-tailored to each specific electorally important state or constituency?

And as for all those other campaign issues, almost all of them can be subsumed within the wider climate debate, or at least viewed in ways that render the climate component crucial. Black lives matter, to be sure, but that’s all the more reason to foreground environmental-justice initiatives. This current pandemic may well turn out to be just the first of many more occasioned by mankind’s relentless encroachment on nature. If you think tidal migrations are politically destabilizing now, just wait until the migrations necessitated by the rising seas caused by polar melts or the narrowing zones of habitability caused by droughts, their attendant firestorms, and the ensuing wars for arable land really begin to kick in. And as for that Supreme Court seat, how might that new justice affect the fate of the climate initiatives that a mobilized popular climate response will need to be marshaling forth?

In the end, perhaps the sole good thing to be said about the sorts of massive climatic disruptions that are just beginning is that the only way we are going to be able to avoid their compoundingly horrendous sequels is to contrive a way of living that is in fact much, much better than the one we have now. And really, we have no choice but to do so.

So damn Scylla and Charybdis, denial and despair!

And determined, engaged: Full speed ahead!