The Weekly Planet: Why a Climate-Denial Coalition May Be Cracking Apart

And the world’s largest polluter plans its next five years.

Every week, our lead climate reporter brings you the big ideas, expert analysis, and vital guidance that will help you flourish on a changing planet. Sign up to get The Weekly Planet, our guide to living through climate change, in your inbox.

Last week, China released the draft summary of its next five-year plan, its comprehensive economic planning document for 2021 to 2025. It’s an important document, a kind of “plan of plans” for the country’s provinces and agencies. Given the influence that China exerts over the planet’s climate—it emits 28 percent of the world’s carbon pollution, nearly double the share of the United States—the plan should command the attention of everyone who cares about the climate.

The plan pledged to virtually end the country’s heaviest air-pollution days by 2025, an important public-health goal for China’s poorest residents. Which was good timing: A few days after the announcement, the largest dust storm in a decade swept across the Gobi Desert and into Beijing. The storm, which arrived after weeks of intense smog, sent the amount of toxic particulate matter in the air to 20 times above its recommended limit.

But that pollution goal means little for the climate. And honestly, the plan did not exactly reveal a hidden torrent of climate ambition. It referred to a “carbon cap,” but did not specify what it would be. And though the plan pledged to reduce China’s “carbon intensity”—the amount of carbon dioxide emitted per unit of GDP—it was already making those cuts, according to the analyst Lauri Myllyvirta.

I’m not a China expert, so I am always nervous about these analyses. Add to this that there seems to be no official English-language version of the five-year plan, which means that I am cribbing off other people’s translations.

But China is crucial to understand for anyone who cares about climate change. The country is essential to global decarbonization. It leads in the heavy industries that will be hardest to decarbonize, pouring 60 percent of the world’s cement and forging more than half of its steel. And its decisions reverberate around the world. Last year, amid a diplomatic battle over the origins of the coronavirus, China banned coal imports from Australia, sending some of its mines into a doom spiral.

Last September, Xi Jinping surprised the UN General Assembly by unilaterally vowing that China would aim to reach net-zero carbon pollution by 2060. The announcement reframed climate geopolitics; the economic historian Adam Tooze asked if Xi had just saved the world. It certainly reframed Asian climate politics. By the end of October, Japan and South Korea had both pledged to reach net-zero by 2050. These initiatives by themselves set off a boom in green investment that was accelerated by Joe Biden’s win.

But then equilibrium reasserted itself. Tsinghua University released an official study demonstrating that China could reach its 2060 goal by staying on a glide path that could charitably be described as moderate … and uncharitably termed lugubrious. That is, China could continue to increase its carbon pollution through 2030, the researchers said. Only then would it need to begin sharply cutting pollution.

The new five-year plan seems to match that logic. You can read bright spots in it—such as its direction to build 18 new gigawatts of nuclear energy, according to Myllyvirta—but mostly it shows a holding pattern.

You can understand this in a few ways. The first is that China’s leaders are waiting to see what the Biden administration does. Xi could have plans for a 2025 emissions peak, say, in his back pocket, and he could unveil them at a future climate summit. The Biden administration has said it will publish America’s new international climate commitment by the end of April; it is also vying to pass a climate-infrastructure bill in Congress.

Another view is more cynical. The 2060 announcement—and the lackadaisical commitments that have followed—have succeeded in taking the heat off China without committing it to any near-term action. It gets some running room in the grand game that its leaders (and America’s leaders) see it as engaged in. And if the U.S. and the European Union do sign on to a rapid program of decarbonization, well, then China will benefit too. Chinese companies control at least 60 percent of the global capacity for manufacturing solar panels; the Chinese electric-vehicle market is the largest in the world. Those firms will be happy to sell.

A Crack in a Major Climate-Denial Coalition?

If you read a lot of climate commentary, you may get the sense that the fossil-fuel industry, working essentially as a rogue actor, is singularly responsible for America’s lack of climate policy. This isn’t necessarily … wrong, but it’s not exactly correct either. Since the modern era of climate politics began, in 1988, the fossil-fuel industry has worked as a kind of political nexus, a place where lots of different interests—steelmaking, automaking, organized labor—come together to pursue the same goals.

One of the best examples of this can be found in America’s freight-railroad industry. There is nothing inherently noxious about moving goods by rail. Shipping by rail is actually far more energy efficient than shipping by truck. Yet for the past 30 years, the country’s four largest freight-railroad companies have been among the biggest opponents of climate policy in the United States.

I wrote about their decades-long campaign in late 2019. These railroads—BNSF Railway, Union Pacific, Norfolk Southern, and CSX—have joined or funded efforts to attack individual scientists, cast doubt on research, and reject reports from major institutions, such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

All four companies also for years belonged to the pro-coal lobbying group America’s Power, which trafficked in open denial and called climate change a “hypothesis” as late as 2014. Even as several utilities fled America’s Power over its politics two years ago, the railroads remained.

Or they did, at least, for a little while, anyway. BNSF and Union Pacific told me this month that they have finally left the group. Their logos have also disappeared from the trade group’s website.

CSX and Norfolk Southern remain members of America’s Power, according to its website.

At the same time, the American Association of Railroads, a trade group that represents the freight-rail companies and also Amtrak, has rebranded itself as a climate warrior. From a historical perspective, this is pretty significant. The rail association helped establish America’s Power in 2008, and for years it barely mentioned “climate change” in its communications. Now it brags that “the nation’s railroads want to be—and must be—a part of the solution to climate change.”

I’m not naive about what any of this means. The Biden administration is contemplating a major infrastructure bill this year; the freight railroads would love a cut of that ribeye. Worse, they’re not wrong that freight rail probably needs to play a larger role in a decarbonized America.

Nor do I think it is the end of what some activists call “climate delay,” the tiresome opposition and nitpicking of any climate proposal. The Wall Street Journal reported earlier this month that the American Petroleum Institute, oil’s mouthpiece in Washington, is close to endorsing a carbon tax … but even if it does, I don’t expect that it will warm up to any other climate policy.

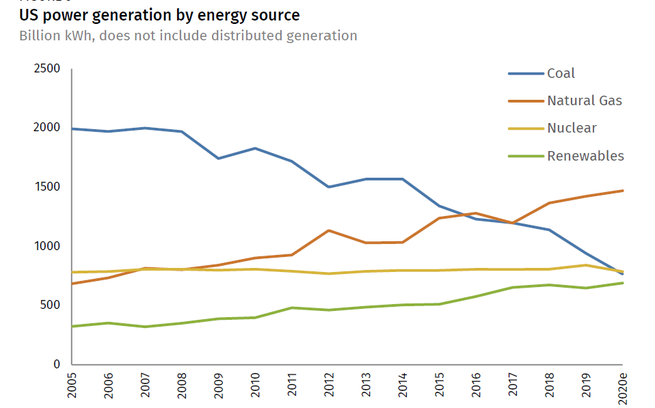

At the core of railroads’ opposition to climate change was their reliance on coal’s business. Coal makes up nearly one in three tons of rail freight. Yet the coal industry is in free fall. During the first half of 2020, coal generation dropped by 30 percent compared with the year before; coal now generates only about a fifth of U.S. electricity. The financial industry is also fleeing coal. Just this week, Citi announced it would no longer fund any company with plans to expand thermal coal operations after 2021—and even more important, the huge insurance firm Swiss Re said that it would stop insuring coal plants by 2040. Freight railroads will need to find new customers, which means finding new political allies. They will look on the left if need be.

Someone Else’s Weather

Our reader Steve Lavender shared this sun-pierced downpour in Renton, Washington, last week. “What I like about this photo is that it appears like it is only raining on my street, so I guess this is more about my weather than someone else’s,” he writes. That’s okay, Steve, it still counts.

Every week, I feature a weather photo from a reader or professional in this part of the newsletter, because the climate is someone else’s weather. If you would like to submit one, please email weeklyplanet@theatlantic.com.

3 More Things

1. Deb Haaland was confirmed as the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, meaning that she will oversee crucial decisions about whether fossil fuels can be drilled from federal land over the next few years. A member of the Laguna Pueblo, she is the first Indigenous Cabinet secretary in American history. (Have I recommended Julian Noisecat’s story about the nomination yet? If not, go read it!)

2. Something I’ve tried to suggest in my coverage of Biden’s stimulus bill is that it represents a break with past ideas not only about how to fight economic downturns, but also about how the economy works. The economist J. W. Mason explains eight of those new ideas in a new blog post. He also describes how many of those ideas aren’t reflected in college macroeconomics courses yet. I really recommend it to people who are interested in the ideas shaping American policy right now—this stuff matters for climate policy, because it will shape how Democratic lawmakers shape a climate bill.

3. Something weird is happening in the electric-vehicle industry: Until recently, every public EV company was doing pretty well. At the end of January, the value of the eight largest electric-car makers stood at $1 trillion, nearly equal to the value of the traditional automaking sector, even though EV makers sell vastly fewer cars.

In a new report, the market-analysis firm Research Affiliates argues that the auto sector is subject to a “big market delusion”: Investors know that at least one of the EV companies will do well in the future, so they’re betting that all of them will do well. They’re also betting that the traditional automakers will do well, too. The bet is that every firm vaguely connected to automaking will do well. It’s a sign that, even if climate tech is the future, the stock market may be treating it like tech firms in the 1990s, a little too exuberant about its prospects.

I’ve been thinking recently about a parable described by the reporter Jamie Powell. In March 2000, investors bet that the enterprise-computing company Cisco was central to the future of American business. They valued it at $80 a share. And they were right; Cisco was the key to the future of American business. Over the next 21 years, it sold a lot of software, and its profits quintupled to $11 billion a year, Powell reports.

But Cisco’s share price never regained the lofty heights of 2000, and today its stock is a little more than $49 a share. Cisco was the future in 2000, but it was also a terrible investment. The same fate may meet EV firms today. The key is to make sure that any future market gyrations don’t imperil the speed of America’s decarbonization.

Thanks for reading. To get The Weekly Planet in your inbox, sign up here.