The Weekly Planet: Why a Political Philosopher Is Thinking About Carbon Removal

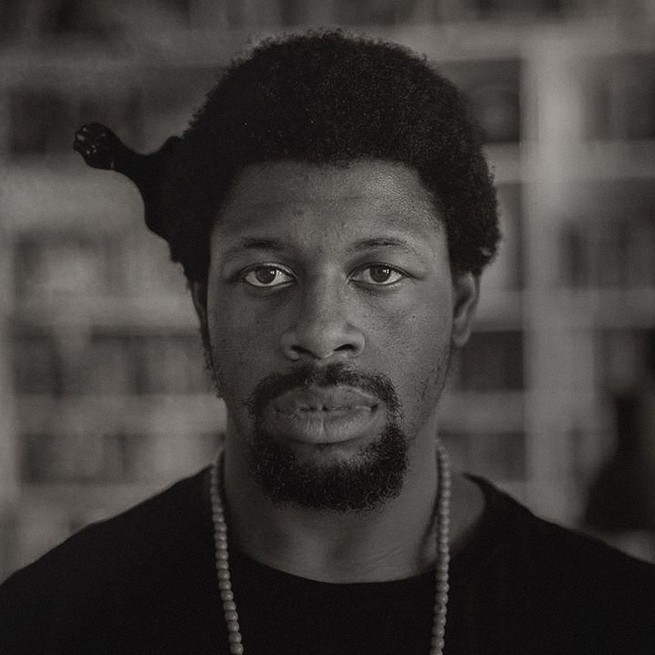

Rich countries should mop up their climate pollution, the Georgetown professor Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò argues.

Every Tuesday, our lead climate reporter brings you the big ideas, expert analysis, and vital guidance that will help you flourish on a changing planet. Sign up to get The Weekly Planet, our guide to living through climate change, in your inbox.

Until a few years ago, the idea that humanity could suck carbon pollution out of the atmosphere at an industrial scale was deemed implausible, if not impossible. The technology didn’t exist to do it, and even if it did, scrubbing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere posed such huge thermodynamic problems that the endeavor seemed prohibitively expensive.

For this reason, the possibility that we might one day use technology to address the root cause of climate change seemed like science fiction—and possibly science denial.

Then, in 2018, two things changed. First, in June, the Harvard professor David Keith and his colleagues argued that they had dramatically reduced the cost of capturing carbon dioxide from the air. Their method wouldn’t by itself resolve climate change, but in time, it could help address some of the hardest-to-decarbonize activities.

The second change came in October, when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said that the world could not limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius without some form of carbon removal.

Since then, public interest—and private investment—in carbon removal has surged. Oil companies have lumbered in. And the conversation has become much harder to track. Is carbon removal an important tool in an all-out societal war against climate catastrophe? Or is it, as many on the left now intimate, a mere fig leaf for polluters, a “dangerous distraction” pushed by billionaires that reveals the limits of gradualism in fighting the climate crisis?

Maybe it’s none of the above. “I feel like, as a philosopher, I can say with some authority that folks are really just overthinking this. They are overthinking it,” Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò told me recently.

Táíwò is a political-philosophy professor at Georgetown University who studies environmental justice. He has warned of “climate colonialism” and called for some form of climate reparations to help the world’s most vulnerable people achieve self-determination in the face of climatic upheaval. He is also a very funny Twitter user. And in a tweet last month, he expressed frustration with how carbon removal is often discussed online, comparing the global North’s historic carbon pollution to a milk carton spilling on the floor. Some leftists, he implied, would rather talk about replacing the floor than just pick up a mop and start cleaning.

That tweet alone was enough for me to call him. We talked about why, as a philosopher, he started thinking about carbon removal in the first place—and why justice-concerned activists shouldn’t get tied in knots over the nascent technology. Our conversation, which follows, has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Robinson Meyer: How did you get into thinking about climate change in the first place?

Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò: I kind of backed into it from more orthodox questions about political philosophy. I was thinking about Pan-African politics, and thinking about issues like public health, and education systems, and economic systems—trying to figure out what things made sense to do on a short-, medium-, and long-term basis. And anytime I got to medium- or long-term, I ended up backing into the climate question. How hot is it going to be? What will the sea level be? What will the rate of desertification of the Sahel be?, for example.

And after having that happen a bunch of times, it occurred to me that I really needed to be thinking directly about [the] climate crisis and climate justice, because it was going to be decisive for a lot of these social issues.

Meyer: There’s a sense that philosophy is about eternal truths, but carbon removal is a specific new technology. Why is a political philosopher thinking about the specific capability of carbon removal?

Táíwò: A couple things. First, there are strains of political philosophy which are more focused on formal relationships between people and institutions—whether laws are well constructed, whether communities have good relationships.

But there are traditions of political philosophy that are focused more squarely on arrangements of power between people. And the Black radical tradition, anti-colonial traditions, anticapitalist traditions are in that broad family—and that’s the kind of political philosophy I do.

So I’m not interested in whether carbon removal is something Locke would have remarked upon. Those aren’t the political questions I ask. I ask, How are people meeting their needs or failing to meet their needs? Who’s responsible, and what should we do about it? And it will always be relevant from that perspective. I ask what technologies are out there, how we’re producing things, how we’re responding to our ecological and geopolitical realities. Most critically for the kind of philosophy that we’re doing, How should you distribute things—responsibilities, burdens, resources? That’s all crucially at issue with climate justice.

Meyer: If there were one idea that you wish people carried into conversations about carbon removal, what would it be?

Táíwò: I think the biggest thing people need to keep track of in these conversations is that what matters is outcomes, not sides. The basic problem with the carbon-removal conversation—as I perceive it—is that people are trying to read off of who supports what [to know which position] they should support.

Meyer: In other words, people associate carbon removal with what a certain company wants, or a certain political party wants, so they oppose it.

Táíwò: Yeah. I mean, they’re thinking well, but about the wrong set of questions. Because it just is true that there are concerted political actors who are trying to use the possibility of carbon removal to protect their agenda, which is decidedly not green. And many of those are fossil-fuel companies and state actors.

I think there’s a more basic kind of political mistake, which is thinking that a political adversary is someone who, on every constituent issue, has the polar-opposite interests of what you have. And that’s just not how politics has worked or will ever work.

So … how do I put this? I feel like, as a philosopher, I can say with some authority that folks are really just overthinking this. They are overthinking it.

Meyer: [Laughs.]

Táíwò: They are really just overthinking it. Like, a section of the world that has the lion’s share of economic, political, and interpersonal security, and that has the lion’s share of wealth, has also emitted the lion’s share of pollution. And now there are ways emerging to literally, in direct ways, address that pollution; ways of removing pollutants from the air and putting them someplace else where they can do less damage to the world.

Just turn the galaxy brain off. That’s actually a good thing that should be happening.

And there are complicated questions, yes, to ask about how that should be happening. Different ways of rolling that out that could go wrong. But just keep it simple. Pollution: bad. Removing pollution: good.

Meyer: Just to steelman this, even if Exxon is running ads saying, “Look, we can remove pollution! We’re investing in pollution-removing tools!”

Táíwò: Again, it’s bad for them to run the ads, but you shouldn’t make the world worse so that they don’t get to brag about making it better. We can just accept these two things: Greenwashing is bad. Also, leaving pollutants in the air is bad.

Meyer: [Laughs.] Yes.

Táíwò: One kind of example I always point people to is just the realities of cross-imperial competition, right? When the Haitian Revolution was happening, there was support for it from both the competing empire of England and competing capitalist interests who were operating in the East Indies with other forms of unfree, highly coercive, highly exploitative labor.

If someone told Toussaint-Louverture that he shouldn’t want the Haitians to be free because that’s playing into [British] hands—that would be very strange. That’s a weird take. That’s not the lesson to learn from what Bad Guy No. 2 is saying to Bad Guy No. 1.

You actually have to do politics yourself. You can’t read it off of what the bad guys are doing. You have to decide what you’re interested in and what’s going to serve the cause of justice. And that’s not just negating things that your adversaries say.

Meyer: On Twitter, the climate-policy expert Michael Thompson once shared a thought experiment where there’s a technology that can restore atmospheric CO₂ to 350 parts per million (which is the “normal,” pre-climate-change amount of carbon dioxide). He says, Okay, there’s not such a technology, but if one appeared tomorrow, would your politics require you to oppose it?

Táíwò: That’s a great thought experiment. [Laughs.] Because it really focuses on what’s going to happen to the world and to people—and not just to our battle of words with the people we don’t like, on the other side of an argument. And once we relocate the conversation there, everything in this space gets a lot more obvious.

Someone Else’s Weather

Our reader Andrew Parker shared this photo of a snowy sunrise in Middleton, Wisconsin. You can almost smell the wood smoke in this one.

Every week, I feature a weather photo from a reader or professional in this part of the newsletter, because the climate is someone else’s weather. If you would like to submit one, please email weeklyplanet@theatlantic.com.

11 Things in a New Democratic Climate Bill

Last week, I wrote about how lawmakers were beginning to shape the great climate bill of 2021.

Now the public step of the shaping has begun! Today, Democrats on the House Energy and Commerce Committee released a new draft of the CLEAN Future Act, their signature climate proposal. You should understand this as Democratic House moderates’ opening bid to shape whatever eventually becomes law. The new bill includes:

- “A National Climate Target” for the United States to cut climate pollution by 50 percent from its historic peak by 2030 and to “net zero” by 2050

- A Clean Electricity Standard, which would require 100 percent of U.S. electricity to be carbon-free by 2035

- A new legal requirement under the Clean Air Act that each state devise its own plan to meet those goals

- New powers for the federal government to build out the power grid

- New energy-efficiency standards, including a “Climate Star” program modeled after “Energy Star”

- A new Office of Energy and Economic Transition in the White House to help fossil-fuel workers and communities

- A new federal lead-removal program.

It also dedicates $565 billion in funding over 10 years to accelerate America’s “deep decarbonization,” including:

- $100 billion for a new “green bank” that will mobilize other money and help firms and local governments decarbonize

- $25 billion to buy electric school buses

- $20 billion to reduce climate pollution from seaports

- $8 billion for home energy-efficiency retrofits

- $1.25 billion to plug methane leaks from the country’s natural-gas infrastructure.

Forty percent of funds under the act must benefit “environmental-justice communities,” a term that is left artfully undefined. Most important, the bill is not written to survive the Senate’s reconciliation rules, so—assuming that the eventual bill would receive a party-line vote—it would need to change significantly before it could become law. But this public debut should make clear that Democrats’—and America’s—new attempt to pass a climate policy has begun. Perhaps the third time will be the charm.

Finally, some late-breaking news: The Swedish automaker Volvo has announced that it will stop making gas-powered cars by 2030. General Motors said in January that it would go all-electric by 2035.

Thanks for reading.

I’ve been listening to “Skyline,” a melancholy but charming new track from the Italian jazz combo dBus. If you have thoughts on carbon removal, Democratic policy making, or Italian jazz, reply to this email or send me a note at weeklyplanet@theatlantic.com. Thanks, as always, for reading.