The Techie Dissidents Who Showed Egyptians How to Organize Online

The April 6 Youth has been instrumental among Egypt's pro-democracy movement in using digital technologies to help build momentum that's led to the widespread revolt now underway

Three summers ago on a litter-strewn beach in Alexandria, I tagged along with a group of young Egyptian dissidents for a little civil disobedience. The goal was to fly a kite painted the colors of the country's flag, and hand out pro-democracy leaflets. They also considered singing some patriotic songs.

Three summers ago on a litter-strewn beach in Alexandria, I tagged along with a group of young Egyptian dissidents for a little civil disobedience. The goal was to fly a kite painted the colors of the country's flag, and hand out pro-democracy leaflets. They also considered singing some patriotic songs.The gathering was broken up almost instantly by at least a dozen security officers, most of them in plain clothes and many sporting mustaches. Everyone was gone from the beach in a matter of minutes.

Those same young men and women are now at the epicenter of events that have brought Mubarak's regime to its knees, and may catalyze a wave of civil unrest and demands for political accountability across the Middle East. It is day 10 now, but soon enough, people may be talking about the sixteen days that shook the world. When they do, they will want more details about who made it happen, and how.

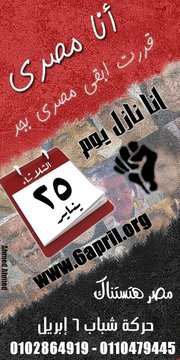

One behind-the-scenes cog is a quiet civil engineer named Ahmed Maher. In 2008, Maher, together with a woman named Israa Abdel-Fattah, launched a Facebook group to promote a protest planned for April 6. In a matter of weeks, they had 70,000 members.

They called themselves the April 6 Youth. In Mubarak's thuggish regime, a gathering of more than five people could land you (or could have landed you?) in jail if you didn't have a permit. So the young activists did their assembling online, where they shared their unapologetic idealism. They wanted fair elections, freedom of expression, jobs, and the possibility of a more prosperous tomorrow.

During the April 6, 2008 protests, Abdel-Fattah was arrested and imprisoned for two weeks. Based on the country's emergency law, in place since 1981, Egyptian authorities have the power to hold citizens without any charge under a "detention decree." But local newspapers and foreign media pounced on the story--they dubbed her "Facebook Girl"-- and the arrest quickly inspired new recruits to join April 6 Youth. A few months later, Maher was also arrested--and tortured. The popular response was much the same: a heightened profile for the techie dissidents, and intensified frustration on the part of their peers, their peer's networks, and those networks' networks.

Wael Nawara, cofounder of the El-Ghad Party, has closely followed the April 6 Youth and the role of digital technologies in building the momentum that led to the colossal revolt now underway. "This has been a long and painful path," he wrote in an email from Cairo yesterday, where many people are now, finally, back online. "But surely the technology--and the Tunisian experience--helped jump-start the revolution."

In 2009 and 2010, while westerners debated whether the internet hurts or helps political dissent (it does both, of course), and even speculated that social media has only a nominal role to play when it comes to substantive social change (clearly false), Maher and the April 6 Youth were hiding out in various Facebook groups to evade detection, bouncing between aliases on Twitter, plotting small-scale protests, digitally corresponding with like-minded souls in neighboring countries, and spreading their uncomplicated message: things could be different. Then Tunisia happened. Then Jan 25. And then Mubarak shut off the Internet.

I have spoken with Maher a few times by phone this week. A number of his friends were just arrested, but they were still trying to plan their next peaceful protest. Picturing him standing amid the chaos in Tahrir Square, I see the messenger bag draped over his shoulder, and the sunglasses. Perhaps they are the same ones he wore that day on the beach in Alexandria, back when I believed I was witnessing some brave, but ultimately quixotic, kids. They believed they were laying the foundation for revolution.