Children are weird. I was going to say “most children,” but I think this a rare universal law. The world is algebra, and young minds are solving for many different unknowns. Children’s literature — the product of adult guesswork — often fails to account for its audience’s slippery grasp on the world. Kids find sad things hilarious (laughing when Charlotte dies after spinning another web) and humor to be frightening (cowering at Seuss’s hectoring goldfish). Some writers understand this, and understand too that kids hear music (much like Cylons; I’ve long suspected my kids are aliens) and need books that sing to them. Maira Kalman writes such books.

Not all her fans think of Maira Kalman primarily as a writer, but that’s how she described herself to me when we met last month. “How do I combine this writing and this art to say as much as I can with as few words as I can: I knew I wanted to do that, and there’s a history of that, especially in children’s books, where you have a certain kind of freedom to play that you don’t have as much in working for adults,” she said.

My excuse for writing about Kalman is the reissue of several stories for children that she published in the 1990s, starring a dog called Max. (She’s got a new book, too, Cake, a collaboration with the food writer Barbara Scott-Goodman.) In those texts, her other work for children, and her work for adults, Kalman is the remix artist she describes above, one for whom image and word are intertwined and of equal importance.

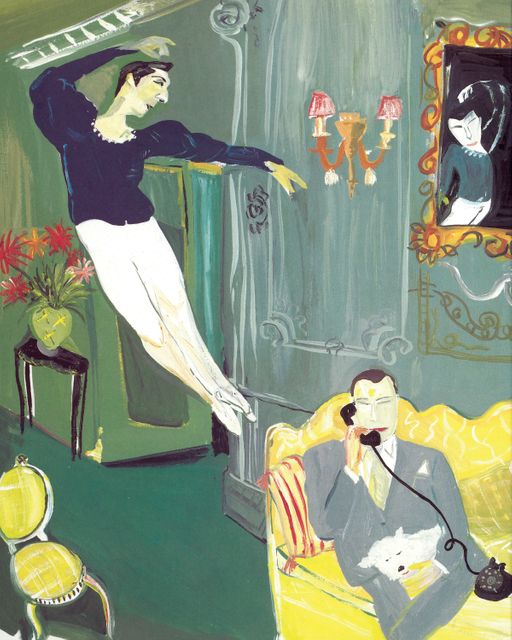

Artists who do this cause consternation; should a book by Maira Kalman be covered by an art critic or a literary one? Her paintings are well known thanks to The New Yorker (the 2001 cover “New Yorkistan,” a collaboration with her boyfriend, Rick Meyerowitz, has attained a status approaching Saul Steinberg’s “View of the World From 9th Avenue”). She’s also been a columnist for the Times, collaborated with choreographers, created an installation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, performed in Peter and the Wolf (she played a duck), and run a pop-up shop. Kalman is one of those only in New York, kids, only in New York oddballs who somehow embodies the place. If you most often hear her described as an illustrator, I suspect that’s because it’s easier than explaining what she actually is.

In The Principles of Uncertainty, a collection of her columns that appeared under the same name in the Times, Kalman writes, “You might notice that there are ten suitcases in the middle of my living room. ‘Going on a trip?’ you might ask. ‘No.’ One of them belonged to a man who fled Danzig in 1939. As if I need reminders of the Holocaust. That’s all I think about.”

I met Kalman in her Greenwich Village apartment, which looks as anyone who knows her work would imagine it: a trio of fezzes atop an upright piano, some cold water in a carefully chosen minimalist drinking glass, and the aforementioned suitcases.

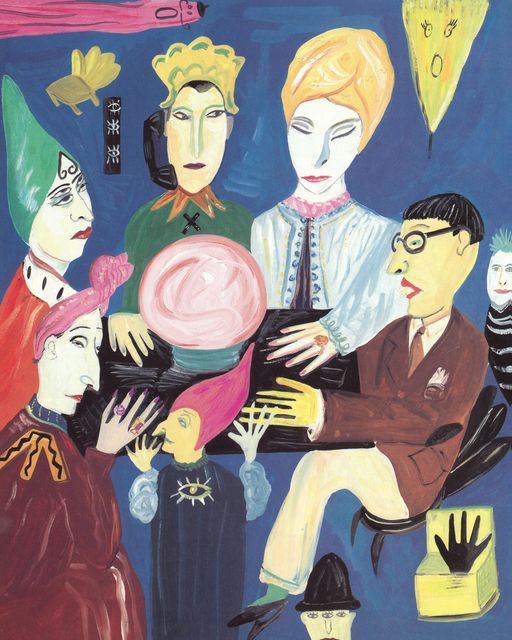

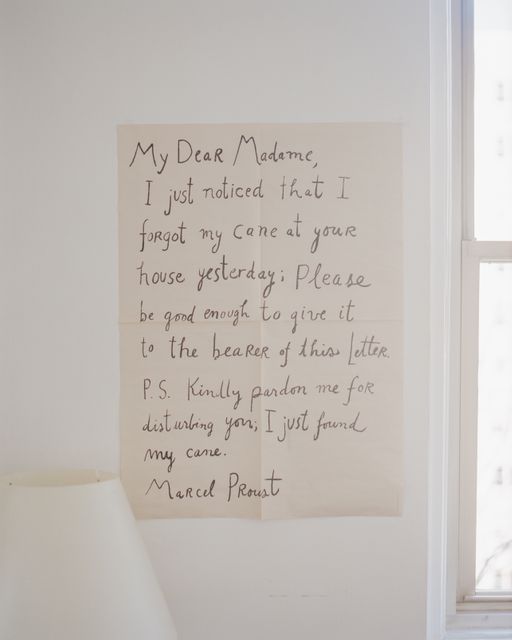

I mention the suitcases because they are evidence that there is little distinction between Kalman’s actual and textual selves. Yet if her readers feel they know Kalman via her various hobbyhorses — cake, the American Founding Fathers, Proust, absurdly appointed historical rooms, fanciful hats — all they really know is these totems. There are those creatures of fashion and style who are little more than a collection of images and interests, sentient inspiration boards, and Kalman is decidedly not that (even if she loves painting pictures of shoes). I asked her to define her territory as an artist. “I think that it’s clear that it’s inquisitive, digressive, lyrical, humorous,” she said. “There’s the duality of the sorrow of the moment and the joy of the moment, which I see very acutely all through the day.”

The very prettiness of Kalman’s pictures and the whimsy (a loaded word, I think, but applicable if you understand whimsy can contain meaning) of the subjects to which she’s drawn can disguise or obscure that sorrow. She is an artist who notices, and the things that catch her eye lead to the most unexpected revelations. When she writes of thinking about the Holocaust every day, it feels like a joke and the truth.

In her work for adults, Kalman is almost a diarist, which breeds a certain deceptive sense of familiarity. “I’m up-front in the sense that I’m letting you be part of what I see,” she told me. “And things I think. I mean, it’s not so intimate that you know my life. But it is intimate in the sense that somebody’s really talking to you about life.”

The bare bones of her life, gleaned from our conversation and her books: Kalman was born in Israel, in 1949, and her family relocated to the States when she was still a toddler. She was raised in Riverdale, and studied at NYU. It was there that she crossed paths with Tibor Kalman.

“We met in this class of misfits in summer school,” she told me. “They said, You have to take these classes, otherwise we’re going to throw you out. What was interesting was the mix of crazy people in that group — like wow, this is the most fun I’ve had in all my time at this horrible NYU place. So we met there, and he asked me out on a date. And you know in your life, when you meet somebody [and] you go, ‘I’ve known you for a thousand years,’ and there’s not even an iota of a question?”

They married in 1981, and Tibor would go on to fame few graphic designers achieve. He was the editor-in-chief of Colors, a seminal print magazine in an era where such a thing was possible, created the cover of the Talking Heads record Remain in Light (it’s in the MoMA now), and designed the freebie postcards and matchbooks at Florent, which was once the absolute ideal of a New York neighborhood restaurant and has since become a Madewell store.

These projects were officially the business of M&Co, and of that firm’s work, Colors is probably the best document of Tibor’s radical vision: that design must be judged not just by its audience but in terms of its impact on the environment and the laborers who executed it. M&Co’s irreverence makes them the grandfather of the many contemporary design firms that are ironic about the fact that they’re in the advertising business. But Kalman’s was a rigorous practice of social critique; even today’s most aggressively twee design shops are thrilled when Mercedes-Benz or R.J. Reynolds comes calling.

It’s worth noting that the initial in M&Co represented Maira. She played an integral role in the firm, but she had a daughter, Lulu, in 1983, and a son, Alex, in 1985; that’s the same year she published her first book, a text for children set to David Byrne’s lyrics for the Talking Heads song “Stay Up Late.” This doesn’t seem coincidental. For so many — particularly women — the arrival of children occasions what Meg Wolitzer termed the “ten-year nap”: a long period in which careers lie fallow while tending to the business of family. For Kalman, that period seems to have given her a new direction, away from advertising and toward books.

Tibor died in 1999, at only 49. “People ask, Well, what would he be doing now?” Kalman told me. “And I say, ‘I don’t know. He probably would have tried to blow up the White House.’ I’m just saying. I’m not sure. Maybe.” Kalman and her son Alex are in the early stages of planning a film about Tibor’s life. (Alex is in the family business; he runs a design studio called What, one project of which is the downtown oddity Mmuseumm, a space only 60 feet square that juxtaposes odd found objects to subvert the very idea of museums and curatorial practice.)

It will be an opportunity to celebrate his legacy and give Maira her due. “I was very content to be behind the scenes when it was comfortable for me to be there,” she said. “We knew what my role was, as elusive as it was sometimes. I will not shy away from saying that I was a vital part of the creative process of the company, and of us, and of our lives.”

Advertising is no longer Kalman’s concern. “I spend more time trying to drown out noise and stuff,” she said. “I like to shuffle around” — indeed much of her work mentions going for a walk — “and I’m in bed by 8:15. Since Trump was elected, my boyfriend Rick and I obsessively watch murder mysteries. I can’t think of a night without one. And all I want to do is hide under the covers, watch a murder mystery. Life is very cocooned. There’s work in my studio. There’s my family. Of course, some friends and a very cocooned, sweet time so I can have my own quiet misery under the blanket by myself.”

In her work for adults — My Favorite Things, And the Pursuit of Happiness, The Principles of Uncertainty primarily — Kalman lays bare the movements of her mind, the way doors make her think of Wittgenstein and the impossibility of certainty. But she is reticent on the matter of her private life. A fan might not know that she has children, but to hear her talk about her experience of motherhood illuminates all of her work.

“When Lulu was born, I said, ‘Now I know why I’m alive.’ Everything before that seemed pretty fine, but to have a child seemed … Now I know what this is all about. So when Alex was born, the house was just fantastically imaginative, and we’d turn all the furniture upside down and make forts in the room and things that would last for days. There was a sense of play that was very active and very real for me.”

This is unsurprising. In Hey Willy, See the Pyramids, Kalman illustrates several stories told by one child to another after bedtime. They have their own peculiar logic, and the linguistic detail — “In front of blue mountains and green mountains a thin skinny man saw fish flying up” — feels like the product of a child’s mind.

“Writing the children’s books wasn’t a piece of cake,” she said. “I understood that it was to be crafted, but the language was natural. I didn’t have to say, Oh, how am I going to write a children’s book? Or how would a child think? I mean, that’s part of the way I think.”

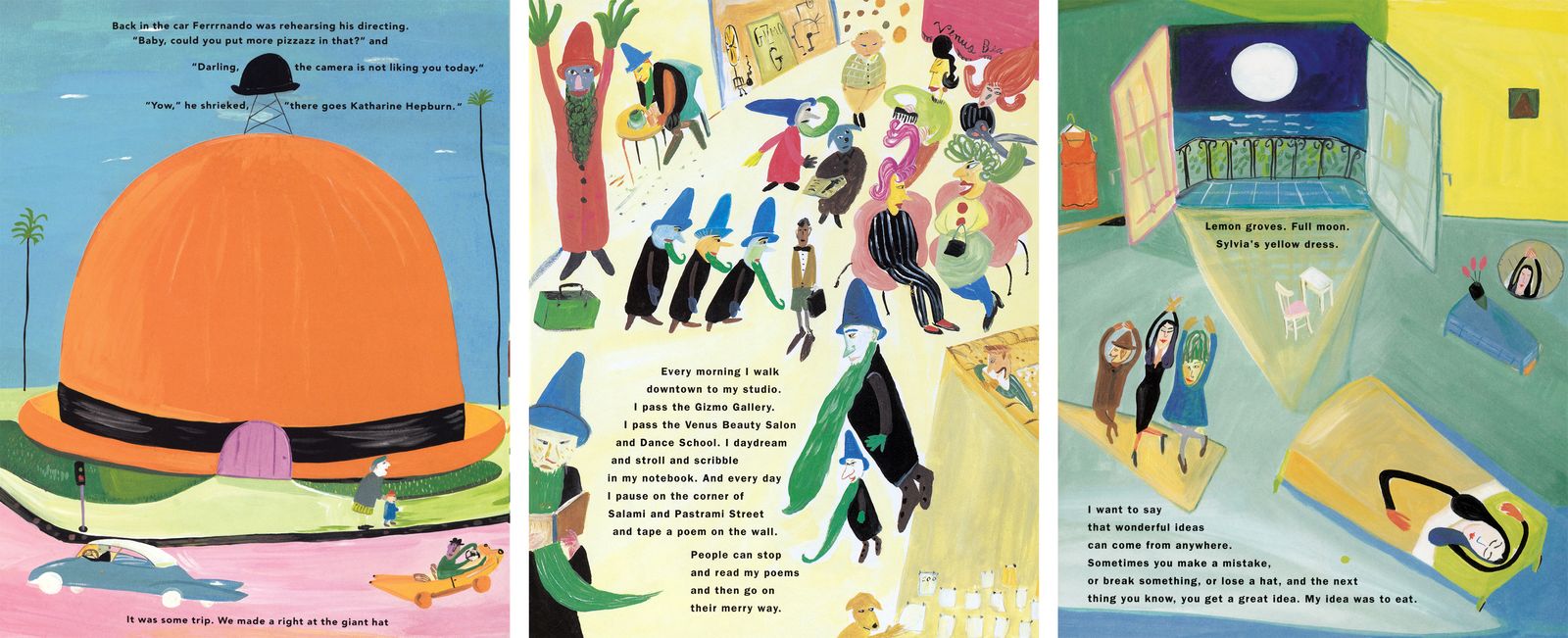

The language is something honed to a very fine edge in the books about Max. The title character is a charismatic dog who happens to be a poet. In Max Makes a Million he sells a book for a fortune (it is fiction) then runs off to Paris. In Ooh-la-la, Max in Love he falls in love with a dog named Crepes Suzette. In Max in Hollywood, Baby he tries his hand at screenwriting.

Kalman’s images reward, but when children are at the age they are read aloud to, it’s the sound of a book that matters most. “Bonjour, Monsieur Max, allow me to introduce myself. I am Fritz from the Ritz which I quit in a snit when the chef in a fit threw escargot on my chapeau and hit my head with a stale French bread.” I can’t read Kalman’s books to my kids at bedtime anymore; they make them laugh too hard.

Much as her work for adults isn’t simply whimsy, Kalman’s books for children are not merely slapstick. “I respect my audience. I really do. I have as much respect for children as I do for adults and probably more,” she said.

In Thomas Jefferson: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Everything, a children’s biography of the statesman, Kalman writes candidly about the man. “It is strongly believed that after his wife died, Jefferson had children with the beautiful Sally Hemings. Some of them were freed and able to pass for white. Passing for white meant that your skin was so light, you could hide the fact that you were partially black. To hide your background is a very sad thing. Perhaps people felt they had no choice in such a prejudiced land.”

“I think that you really can talk to kids about anything,” Kalman says. In Fireboat, she tells of an old ship that played a part in the 9/11 recovery efforts. She does not shy away from illustrating one of Minoru Yamasaki’s towers exploding. This may put off certain readers. But the book succeeds because Kalman is so forthright, the rare adult willing to admit to kids that scary things happen. By giving kids the facts, teasing out of that dreadful day a story of heroism, and telling it in her signature, almost musical style, the book is somehow reassuring rather than frightening.

Children who are read aloud her books may not get the jokes about Hollywood starlets, as they may not get what it means that “The city had been attacked.” But children can sense adults’ discretion, and they appreciate honesty.

“And that’s the way I write for adults, too. There’s really not much difference at all. So I think I just — this is my story,” Kalman said. It’s a simple admission that felt to me like a revelation. Kalman’s works for adults function just like books for children, with profundity disguised in prettiness, the whole thing animated by that particular voice of hers — curious, caffeinated, discursive, inflected by Yiddish, maybe, or perhaps it’s many other tongues, too: the voice of New York City. The day I visited her, I brought along some babka and rugelach from Russ & Daughters. That night, Kalman emailed me: “Very sweet of you to bring the assortment, as we used to say in the Bronx.”

“I met Maira when I was seated next to her at a glamorous dinner in Italy. I conspired to sit next to her after years of admiring her work, and within minutes we were giggling and passing notes on napkins. We have been pals since, almost 20 years,” the writer Daniel Handler told me. “We have a particular soft spot for where suffering and sadness meet the ridiculous. Among other things it is a Jewish sensibility.”

In My Favorite Things, Kalman writes, “The artist Charlotte Salomon lived in this room in Berlin in the 1930s. She painted and wrote about her family in a book called ‘Opera or Life.’ People were always coming and going and dying. She was killed in the Holocaust. Which brings us inevitably to sorrow.”

Salomon is a helpful example. She was a painter interested in beauty, even in work that depicted Kristallnacht. She was also a writer, inscribing text onto the paintings or on tracing paper meant to overlay them. Salomon’s insistence on doing both makes her hard to categorize — should she be thought of as a modern painter or a wartime memoirist?

Kalman is writing of less dire matters, maybe. I suspect, though, that she’s an artist of equal importance, and equally hard to place in the canon. Her curiosity about objects and people is really a curiosity about history and humanity. She understands the larger world, and the way in which it is so frightening. It’s no wonder she goes to bed at 8:15. If there is uncertainty — and really, what else is there — there is also the reassurance of beauty: in the pancakes at a diner, the tassels on some fussy curtains, Abraham Lincoln’s visage, old photographs of anonymous girls standing on unknown lawns. And we could all of us, no matter how old, use a little reassurance.