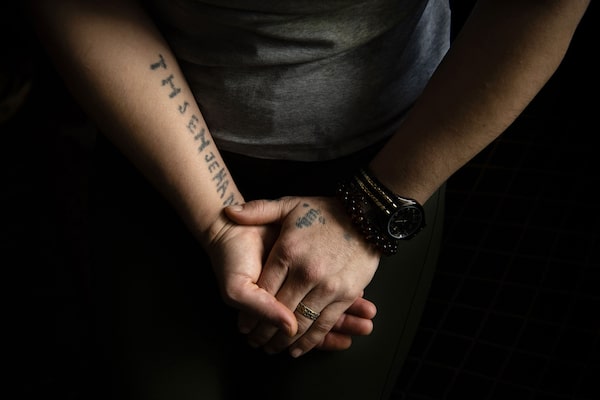

The names of Jihan Khudher’s missing family members and fiancé are tattooed across her upper body. When she was a prisoner of the Islamic State in Iraq, she hoped the markings – considered forbidden by some in Islam – would serve as a shield from her captors’ abuse. Now, she is a refugee in Canada, and the tattoos remind her of a family that was torn apart by the militant group’s onslaught in the Middle East.

Photography by Kiana Hayeri/The Globe and Mail

Jihan Khudher doesn’t remember the first time it happened. She remembers the minutes before. She’d just been raped by the man who held her captive. Then he left the room, locking the door behind him. The next thing she remembers took place some unknown time later. She awoke in a medical clinic. Everyone around her spoke Arabic, not her native language. Her rapist stood beside her. He would not explain to her what happened – telling her only that she had been brought there because she was tired. He took her from the clinic and back to the building where she had been imprisoned.

That was three years ago. Since then, these episodes she can’t remember keep happening.

When they come, she loses consciousness and falls. Her body writhes, her back arches, her head twists violently from side to side. She sometimes bites her hair and crosses her arms in front of her face – leading her doctors to believe she may be reliving a rape. The episodes are physically draining; humiliating to experience; terrifying to watch. To the untrained observer, they look like a grand mal seizure. But unlike epileptic seizures, there is no atypical brain activity driving these spells, thus no medication or surgery that can prevent them or decrease their frequency.

Known as pseudoseizures, Jihan’s episodes are similar to epileptic seizures in symptoms but entirely different in source. They are triggered by extreme psychological stress. In that way, they offer some mercy: For a minute, two, 10, 30, however many minutes or hours they last, she is aware of nothing. She is completely dissociated from the world, temporarily reprieved from her present and past.

Psychiatrist Rita Watterson, right, pays a home visit to check on Jihan.

Jihan, who is 29 and lives in Calgary, arrived in Canada as a refugee in the summer of 2017, as part of the federal government’s Victims of Daesh resettlement program. She and her family were driven from their home in northern Iraq during a brutal campaign of murder, kidnap and rape by ISIS that began in 2014 and targeted Yazidis, a predominantly Kurdish religious minority. Distinct by their faith rather than ethnicity or language, the Yazidis have been subject to as many as 74 attempted genocides over 800 years. About 1,200 Yazidis have come to Canada since the ISIS assault began, living mainly in Toronto, Winnipeg, Calgary and London, Ont. But as Canada tries to create a safe space for survivors, cases like Jihan’s raise questions about how prepared our health-care system is to treat them.

Since arriving from Iraq after 18 months in captivity and another 11 months in a refugee camp, Jihan has been seen regularly by doctors in Calgary who have likened her condition to an extreme form of post-traumatic stress disorder. Her formal diagnosis is conversion disorder with pseudoseizures, or psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES). It’s considered rare, but the disturbingly high incidence among Yazidi refugees has caused concern among Canadian medical and resettlement staff. PNES usually occurs in about 2 to 33 per 100,000 people a year. But in Calgary, for example, 6 out of 300 Yazidis have been diagnosed with the disorder.

And the condition is proving perplexingly difficult to treat. Recommended approaches such as psychotherapy and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) haven’t been effective with Jihan or many other patients. Antidepressants, sleep aids and anti-anxiety medications haven’t decreased the frequency of her seizures. Staff at other medical and resettlement centres have begun experimenting with non-traditional therapies for patients like Jihan, but so far, with limited success. Some have even ended up seeking counselling themselves to cope with vicarious trauma, brought on by the horrifying stories they hear in the process of caring for Yazidi refugees.

In the evening, Jihan and her sister Munifa practise the English alphabet.

Jihan’s care team is now wondering what else they can do to help, and have identified what they believe is a critical component to her future success: The reunification of her broken family. Jihan, who grew up in a seven-member family, arrived in Canada with only one sister. A federal government policy that only allows for spouses and dependents to join successful refugee claimants in Canada means that her second sister must apply separately and hope to be chosen. But without access to more of her family, Jihan may never thrive, say members of her care team who argue that many other Yazidi refugees face the same plight – and should be given special treatment by Canadian immigration officials.

Annalee Coakley, medical director for Calgary’s Mosaic Refugee Health Clinic, describes the Yazidis as “very different from other refugee communities.” Describing her first meeting with a Yazidi family, she says, “I’ve never seen families in acute distress like that. They were having trouble breathing, they were crying, they reported all these horrors. The children were very, very fearful – you couldn’t get close to them to do a physical exam.”

The treatment they need extends beyond medical and therapeutic intervention, says Dr. Coakley, who is asking the federal government to allow more of Jihan’s family to enter Canada. Meanwhile, Jihan’s pseudoseizures are getting worse. She suffers them at school, on the train, on the bus. She’s embarrassed by these attacks, which can last for hours, and fears leaving her house, worried an episode might happen in public. In recent months, she has rarely made it through a week without experiencing one.

Jihan believes she’s safe in Canada, living in a secure clean house in southwest Calgary with year-round Christmas decorations and three Canadian flags on the walls. In the living room, on side tables on either end of a couch, two large frames hold a collage of photos depicting more than a dozen family members, all of whom are missing. Jihan hopes someday some of them will make it to Canada. The staff who support her in Calgary hope this will happen too – indeed, some believe that reuniting her broken family might be the best way they can help her and other Yazidi refugees.

At top, Jihan puts on some lotion in front of the mirror before she leaves the house for school. Later that day, she sits in English class, where all of her classmates are fellow Yazidis who have arrived in Canada as refugees. The sisters socialize with the other students between classes.

LIFE IN CAPTIVITY

It’s late afternoon on a smokey-sky summer day in Calgary when Jihan comes home from English school and pushes open the screen door of the duplex she shares with her sister, Munifa, 26. She plunks down her backpack, plugs her phone into a charger, and greets Munifa and the translator, Kheriya Khidir, with a nod.

On her wrist, she wears a silver medic alert bracelet with the words “conversion disorder with pseudoseizures,” and her Alberta Health Services patient-identification number, which paramedics can use to quickly access information about her case. Some details: This is not an epileptic seizure. Do not restrain. Do not hold her down. These actions can mimic the physical brutality of an assaulter. Make sure she is safe. Put a pillow under her head. Do not admit to hospital unless her seizure lasts longer than 30 minutes or is causing her physical harm.

She tells her story in Kurmanji, a Kurdish language spoken by most Yazidi people. It’s a sad and graphic account, one not unusual among Yazidi refugees. Jihan grew up in the northern Iraqi village of Kojo, where she lived with her parents, two brothers and two younger sisters. Munifa describes it as a poor and difficult life; their father died in a car accident and their mother developed a mental illness.

On Aug. 15, 2014, ISIS arrived in Kojo. The fighters split unmarried women and girls from their families, making it the last time the three daughters saw their mother and brothers, and the last time Jihan saw her fiancé, a local man named Thsen.

Today, the sisters recount what happened without hesitation. Jihan talks so animatedly that it’s clear from her gesticulations, before the translator explains, that their captors ripped the earrings from girls’ ears. Everyone in the room knows that telling this story can trigger a pseudoseizure in Jihan, but she insists on telling it in detail.

“We want the world to know what happened,” Jihan says, pausing only for the interpreter to summarize her words before starting again.

Like many Yazidis from northern Iraq, the sisters only speak Kurmanji. Ms. Khidir, one of only two Kurmanji speakers who resided in Calgary prior to 2017, translated their answers, and the medical details of their stories were confirmed through their physicians with the sisters’ permission.

A photo of Jihan and Munifa's older brother Jihad and his wife, Waheda, remains pasted on one of the many Canadian flags in their living room.

ISIS transported them to a building in Syria, where men arrived daily to select women and girls from what essentially became a market for human beings. After several days, the three sisters – Jihan, Munifa and Hudda, the youngest – were carried to the basement of a house. When three men came for Munifa the next day, the girls screamed and tried to hang onto each other as the men pulled her away. She was held captive in another house, where she was raped and forced to study the Koran and follow Muslim prayers, she says.

Another man came for Jihan soon after, and, in 2015, Hudda was reunited with Munifa for several months before she, too, was sold. Neither Jihan, nor Munifa has seen Hudda in person since. She was 16.

Munifa keeps these photos of younger sister Hudda in her wallet.

Over the next year and a half, Jihan was bought and sold to men who sexually and physically assaulted her, breaking her leg and beating her until she bled. For weeks, she was imprisoned in a room where her captor would arrive with bloodied clothes for her to wash, then sexually assault her. Sometimes, he forced her to watch the rapes of girls, not yet teenagers.

She believes her first pseudoseizure occurred about three months into captivity, but she is not certain of the timing. She doesn’t know what happened during her pseudoseizures while she was enslaved.

She does know this: she feigned conversion to Islam, was granted some freedoms in trade, then escaped. She ended up in a refugee camp in Kurdistan, where she was joined by Munifa two months later, when she too broke free of her captors.

The translator intentionally avoids interpreting questions for Jihan about Hudda’s whereabouts. “I do not want her to fall down,” she says. “I know when she is going to fall down. I can see now that she will fall.”

At home with her sister after school, Jihan prepares a late lunch.

With every movement outside their Calgary apartment, Munifa turns to the window to see what it is.

Jihan meets a Kurdish friend, Asmar, to help Munifa sort out a problem with a missing bank PIN.

A DEEP MENTAL HEALTH CRISIS

PNES is an ancient medical conundrum, dating as far back as 400 BC when Hippocrates differentiated between epileptic seizures and what were later known as hysterical seizures. For centuries, these episodes fell under the catch-all descriptor of hysteria, considered a madness specific to women, a sign of a “wandering uterus” according to the ancient Greeks. Attempts to treat the condition – whose symptoms included crying, screaming, extreme fatigue and, in its most dramatic form, non-epileptic seizures – tended to be gendered, bizarre and cruel. Hundreds of innocent people were burnt at the stake for fears of witchcraft and diabolic possession, and, later, a Dutch physician seared sufferers with a hot iron to distinguish between hysteria and epilepsy. In the late 1800s, French doctor Jean-Martin Charcot began studying hysterical patients closely and argued vehemently against the popular prejudice that hysteria was rarely found in men.

Much of what we know about modern conversion disorders comes from the First World War when shell-shocked men suffered symptoms ranging from deafness to shaking, hallucinations to flashbacks. They were often taken out of combat and admitted to psychiatric hospitals – creating large studies of people with conversion reactions. Physicians learned that these symptoms weren’t isolated to those who’d experienced the concussive effects of an explosion. They often appeared in soldiers who’d witnessed terrifying scenes, and that symptoms became chronic even months after the trauma. One critical discovery: sufferers often re-enacted part of their trauma during a conversion reaction, and these responses, including pseudoseizures, were more likely to occur in people with lower social class and less education owing, perhaps, to a poorer understanding of mental health and its effect on the rest of the body. Perhaps most importantly, soldiers with shell-shock showed the world that conversion disorder episodes represent genuine physical responses to overwhelming psychological anguish.

Most Yazidi refugees brought to Canada were women. Like many Yazidis from northern Iraq, Jihan and Munifa speak only Kurmanji, a Kurdish language.

Conversion disorder tends to express differently across cultures. There are no studies of the condition in Yazidis, but research done in Turkey, not far from Sinjar province where Jihan is from, found that it also commonly presents as loss of consciousness. In other parts of the world, however, pseudoseizures can be a rarer symptom. Pakistani and Indian sufferers report sensations of heat inside their bodies, whereas Dutch people experience motor disturbances such as paralysis and coordination disorders.

In Canada, PNES has been documented among Yazidi refugees in Calgary and several other cities. These refugees have been exposed to nearly all risks for this condition. Conversion disorders occur more commonly among women, and most Yazidi refugees in Canada are women. And they lack education: Nearly two-thirds of female Yazidi refugees in Calgary have completed no formal schooling.

And conversion disorders are strongly tied to other chronic mental-health issues, which this population has in abundance: At least 40 per cent of Yazidi refugees who came from northern Iraq suffer mental-health conditions, and at least one in every four Yazidi women treated at Calgary’s Mosaic clinic suffers extreme PTSD, a condition with similar symptoms to conversion disorder, but is a frequent trigger for the disorder.

A study in Germany of nearly 300 Yazidi survivors of rape shows how deep the mental-health crisis goes in this population: Half suffer depression, 39 per cent anxiety and 28 per cent dissociation. Two-thirds of women experience somatic symptom disorder, a psychological state in which a person experiences physical symptoms that can not be explained by an underlying medical condition.

The severity of the mental illnesses suffered by Yazidi women mirrors the severity of the horrors these women endured in captivity. In a graphic finding, researchers discovered that PTSD increases incrementally with the frequency of rape: In women who endured rape less than 10 times, PTSD occurred in 39 per cent, less than 20 times was 41 per cent, and when it was more than 20 times, it reached 57 per cent. That a scale for “frequency of rape” exists should give the most impartial reader of statistics pause.

Over the past year, many Yazidi refugees in Canada have made progress, says Dr. Coakley. They’ve learned how to stabilize themselves in moments of high stress. They don’t hyperventilate and they stay calm. But many have also relapsed, often when they learn that a relative who was once in captivity is now up for sale, or has escaped, causing a new desperation to be reunited.

In Winnipeg, Nafiya Naso, a Yazidi woman who came to Canada nearly two decades ago and helps resettle refugees, has seen a similar pattern. In October, she watched a Yazidi woman have a pseudoseizure midway through describing how she’d contacted a smuggler to help free her grandchildren.

Jihan’s psychiatrist, Rita Watterson, describes pseudoseizures as a signal that something potentially life-threatening is happening to a person mentally. They are rudimentary indicators of massive stress, a more extreme version of the ways we see people respond to pressure all the time – things such as headaches, nail biting and foot tapping.

Scientists believe this happens because the amygdala, or emotional processing part of the brain, becomes overactivated, and that, in turn, affects a nearby area that helps us execute physical tasks we normally perform without too much thought.

Aaron Mackie, a neuropsychiatrist in Calgary and expert in conversion disorder, explains the process like this: When a person with a minor fear of heights travels to the top of the Calgary Tower and tries to step out onto the glass floor of the 190-metre high observation deck, they immediately struggle to put one foot in front of the other. “The fear area of your brain has fired up and it’s actually jamming the signal for how you take normal steps. That’s the phenomenon happening to individuals when their emotional processing area is so hot that it’s running interference in other circuits and preventing them from working the way they normally would work.”

Jihan's tattoos were inked with ash and breast milk from another prisoner of Islamic State.

A COLLECTIVIST CULTURE

During captivity, Jihan tattooed her upper body, hoping the markings, considered a sin by some in Islam, would make her undesirable to members of ISIS. Using a needle and ink made from a blend of ash and breast milk given to her by another prisoner, she poked several names into her chest and arms: Hudda, her mother, her brothers, her sister-in-law. Her fiancé’s name is spelled out above her heart, with Jihan’s beside it on the right. Her body has become permanent catalogue of all the people she cannot locate.

But for one: Hudda. After Jihan and Munifa arrived in Canada, they learned that Hudda, now 20, was still alive. She now lives in the Qadia Camp for internally displaced persons in Iraq.

Hudda speaks with her sisters by phone almost daily, sometimes crying and begging to join them in what seems to her like a life of luxury. These conversations leave Jihan rattled, and she’s had pseudoseizures after the calls.

Jihan and Munifa, shown above in their living room, spend countless hours on their phones. Munifa's phone, left, has two photos of her mother and a Calgary transit pass behind its plastic cover. Jihan's phone is on the right.

Then, this summer, Hudda’s application to join her sisters in Canada through a family reunification program was denied because she is an adult, therefore not a dependent of her sisters. She now waits to be chosen by the Canadian government from a list of tens of thousands of refugee applicants. In Jihan, the news set off a series of pseudoseizures more frequent and more severe than anything her physicians had witnessed during her first year in Canada, causing her to be hospitalized for several weeks.

She’s since been discharged, but her doctors remain worried. Her biggest stressor, according to Dr. Watterson, is the separation of her family. The psychiatrist points out that Jihan’s inability to focus on anything other than reuniting them is a barrier to treatment.

“She won’t break from this defence of ‘it’s my burden to carry my family, I will never stop worrying about them.’ ”

Now, Jihan’s medical team is asking the federal government to bring Hudda to Canada, arguing that family reunification is the crucial missing component to reducing her spells. Dr. Coakley has made similar requests for relatives of other Yazidi refugees in Calgary. “My belief is that if the community here is shored up, if they have more of their own here, specifically their family, that would help. If we reduce their external stressors, and their biggest stressor is this family separation, I think they would do better.”

Relatives in the refugee camps describe crowded environments, with restricted access to water, health care and education, and little safety. One woman in Calgary keeps a photo on her phone depicting the burned, blackened body of her father-in-law who died when a fire spread to his tent. Yazidi refugees in Calgary, London and Winnipeg have written to the Canadian government describing these grim conditions and appealing for family members still in camps to be brought here.

Among Dr. Coakley’s patients are several mothers who came to Canada with only some of their kids – the others were missing or captive – only to learn that their imprisoned children have been released and are living in Iraqi camps. Those under 18 will be able to join their mothers through the reunification program, but adult children are not eligible. Other women have fiancés or sisters who are still there.

Allison Henderson, a family physician at the Intercommunity Health in London, Ont. who works with Yazidi refugees, also believes their mental health will not improve without family reunification.

“There's only so far we're going to get in terms of medications and even therapy when you're looking at a people group that is systematically traumatized and for whom there is still so much ongoing trauma for the relatives who are missing or known to be in captivity."

Dr. Watterson explains that the Victims of Daesh program initially brought the most vulnerable Yazidis to Canada, who were often single women and many of whom have children. “But we didn’t look at how these women run their lives and what the major social determinants of health are for these women,” she says. “For us in Canada, in our individualistic society, maybe it would be okay to separate families because we have skills and education and we would be able to survive. Women who don’t have these things, who only have their family, it’s a detriment to separate them.”

Researchers in other Canadian cities, as well as around the world, are coming to the conclusion that family separation is severely affecting the Yazidis’ mental health. Their culture is collectivist; they come from large extended families, they bond through strong oral traditions, and many of the songs and stories used in their unique religion recount trauma they have experienced over generations. Psychologists who work with Yazidis report that their collective experience of terror and abuse has historically strengthened their resilience and helped them come to terms with individual trauma.

Nikki Marczak, a genocide scholar and advocate who works with Yazidi refugees in Australia, says that while the population has suffered severe transgenerational trauma, its members passed on that resilience through generations. “In some of my research in how Yazidi women survived and defied their perpetrators, a lot of the tactics that they used might be things that they learned from their own great-great grandmothers, things like protecting young girls by hiding or shaving their hair or covering their faces with ashes.”

In October, NDP immigration critic Jenny Kwan tabled a petition in the House of Commons, calling on the Liberal government to provide more psychological support for Yazidi refugees and to allow their extended family members to join them in Canada. Mathieu Genest, a spokesman for Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen, responded to the petition by saying the government is trying to facilitate family reunification as soon as possible.

Not everyone will agree that allowing more members of Yazidi refugees' families into Canada is fair. Government policy focuses on helping those who are most vulnerable, and family members living in camps in Iraq may not fit this category. But Dr. Coakley argues that the petition is a step in the right direction. “I do not feel like government is doing enough to address family reunification.” She says the government’s response – that it does not extend family reunification beyond spouses and dependants for other refugees – doesn’t make sense for Yazidi refugees and their understanding of family.

Some therapists working with Yazidi refugees advocate engaging with families in ways that conflict with traditional Western concepts of therapy, with a distant professional relationship between therapist and patient. Some approaches Ms. Marczak suggests: sitting down and sharing a meal before attempting any therapy, developing programs such as sewing groups, or creating cultural events that normalize the idea of therapy.

Ms. Marczak and several physicians point out that Yazidis rarely respond to personal queries about themselves with personal answers. If a patient is asked how she is, she’s likely to tell you how everybody in her circle is. If you ask about her personal experience before coming to Canada, she’ll often tell you about the experience of her village, what happened to everyone she knew.

Asked what she wants for her life – where she wants to live, what she wants do – Jihan speaks of her family. “If we are all together here, that is all,” she says. “Even if someone told me to go out and clean the roads, I would do it, happy, if I was together with my sisters.”

In English class, Munifa receives a card assigning her to write a sentence about her sister. Practising vocabulary related to family proves to be painful for many of the Yazidi students in the class.