To describe Osman Kavala’s journey into the Turkish justice system as Kafkaesque would be paying a compliment to the great Czech novelist.

Authorities first detained the businessman and philanthropist at Istanbul’s Ataturk airport in October 2017 as he returned from the south-eastern city of Gaziantep, where he had begun work on a project to help Syrian refugees.

Two weeks later, he was officially arrested on suspicion of attempting to overthrow the government by leading the Gezi Park protests of mid-2013, and also on suspicion of attempting to overthrow the constitutional order by taking part in a July 2016 coup attempt. Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) tends to view the former as a sort of trial run for the latter, and labels anybody linked to either as a terrorist.

In February 2019, after 15 months of detention, Mr Kavala was finally indicted on the first count. A year later, an Istanbul court acquitted him of those Gezi-linked charges. But Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan quickly denounced that decision, and Mr Kavala was re-arrested and indicted in connection to the failed coup. He was acquitted on this charge the next month and again ordered to be released, but the court instead added a new charge of espionage, again linked to the failed coup, and Mr Kavala stayed in prison.

By this time the indictment against him ran to several hundred pages and hinged on random moments such as who he bumped into at an Istanbul restaurant. Despite the European Court of Human Rights (part of the Council of Europe, of which Turkey is a member) repeatedly finding no evidence to support the charges and calling for his immediate release, Turkish courts repeatedly approved Mr Kavala’s detention. In January 2021, an appellate court overturned the Gezi acquittal and that indictment was added to his espionage case.

The latest twist came this August. A Turkish court linked Mr Kavala’s Gezi-espionage case to a separate trial involving Carsi, the leading fan group of Istanbul football club Besiktas. Carsi members played a key role in the Gezi protests, but like Kavala they had previously been acquitted of any Gezi-linked crimes.

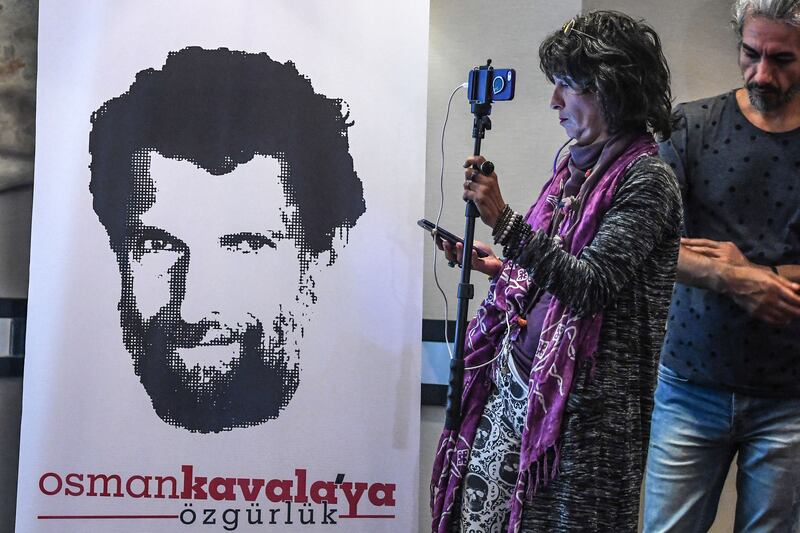

If all this has left you dizzy, you are not alone. Amnesty International has called Mr Kavala’s case a “shocking disregard for fair trial procedures”. Yet this three-legged trial resumed at Istanbul’s vast hall of justice last Friday, where a panel of judges called, yet again, for Mr Kavala to remain in custody.

From his cell in Silivri prison, 40km west of Istanbul, the prisoner issued a searing statement. “What is striking about the charges brought against me is not merely the fact that they are not based on any evidence. They are allegations of a fantastic nature based on conspiracy theories overstepping the bounds of reason,” he said, adding that many of his co-defendant Besiktas fans had no idea who he was. “The joinder with the Carsi case makes this even more surreal. When asked, ‘Do you know Osman Kavala?’ a supporter asked, ‘Which club does he play for?’”

Few could have foreseen all this for Mr Kavala, who turned 64 last week. Having built their fortune in tobacco, his family moved from the Greek port city of Kavala to Istanbul in the population exchange of 1923. When his father died in 1982, Osman broke off his doctorate studies in New York City to take the reins of the family business.

He expanded into publishing, then environmental and civic activism. He founded Anadolu Kultur, an organisation that develops civic collaborations, such as a vast arts centre in the majority-Kurdish city of Diyarbakir, and cultural preservation projects for Yazidis, Armenians and other minorities.

In 2008, he founded a Turkish chapter of the Open Society Foundation, the global pro-democracy organisation of Hungarian-born billionaire George Soros. It is this move, in addition to his prominent place among the country’s liberal elite, which seems to have put Mr Kavala in the authorities’ crosshairs. Turkey’s President has described him as a terror financier backed by “the famous Hungarian Jew Soros”. Asli Aydintasbas of the European Council on Foreign Affairs has described Mr Kavala’s case as a personal “vendetta” that is “unnecessarily cruel”.

Vendettas do make headlines. A recent study found more than 1,700 news articles on Mr Kavala's case over the past four years, in more than 40 countries. Yet his is merely the most prominent of hundreds of thousands of ongoing prosecutions in Turkey linked to the failed 2016 coup, the Gezi protests or other activist movements. Turkish courts are overwhelmed with such cases, and since thousands of judges were dismissed in post-coup purges, many are overseen by young, inexperienced judges.

Most appear to be susceptible to political pressure and thus lean toward guilty verdicts. As a result, Turkey’s prison population is today by far the highest among the 47 members of the Council of Europe. Nearly 1 per cent of Turkish citizens are in prison, compared to less than 0.27 per cent across Europe. The number of university-graduate prisoners has also increased sharply, from 4,400 in 2012 to more than 20,000 in 2019, suggesting increased politicisation. And despite a troubled economy, Turkey’s government has, since the failed 2016 coup, spent $1.4 billion on more than 130 new prisons, nearly doubling incarceration capacity from 180,000 to 320,000.

Next week, Mr Kavala will mark four years of incarceration, despite never having been convicted of a crime. The chances that he might soon gain his freedom remain slim, but one recent development may boost those odds. The Council of Europe last month warned that if Turkey fails to heed the European Court of Human Rights’ legally binding calls to release Mr Kavala, it will begin infringement proceedings.

The Council’s harshest enforcement mechanism was created in 2010 and could lead to the suspension of Turkey’s membership. It has been used just once before. In late 2017, the Council launched proceedings against Azerbaijan, another member state, for its detention of politician Ilgar Mammadov. Eight months later, Mr Mammadov was a free man.