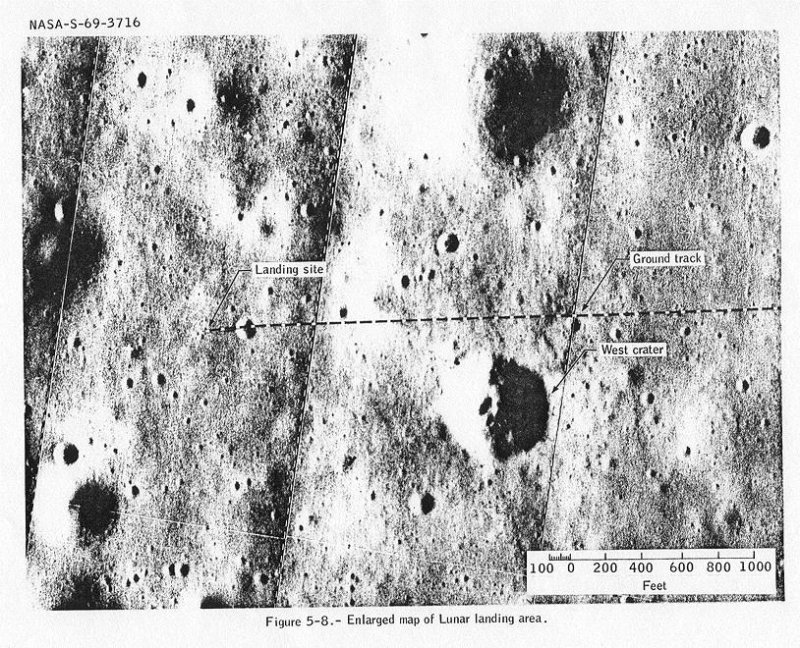

This labeled version of 1:5000 LM Lunar Surface Map LSE 2-48 shows the ground track and the landing site about 60 meters west of Little West Crater. The grid squares are 50 meters on a side. File photo by NASA

SPACE CENTER, Houston, July 19,1969 (UPI) -- A tense, silent, 35 minutes elapsed between the time that Neil Armstrong, Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin and Michael Collins disappeared behind the moon and the time their moonship re-established communications with earth.

A recalculation Saturday revealed that Apollo reached the moon 4 minutes and 39 seconds earlier than expected. This means Sunday's touchdown and Armstrong's first step on the moon will occur that much sooner.

First indication the spaceship had attained lunar orbit came at 1:48 p.m. EDT in telemetry signals received at the Madrid, Spain, tracking station rather than through voice communication.

Then, through heavy static, the astronauts' voices could be heard over the ground control network reading off the engineering figures on the performance of their main rocket engine. The engine consumed 12 tons of fuel in the burn that triggered them into the 70 by 194 mile high lunar orbit.

After adjusting the spaceship's antenna alignment, the astronauts voice came through loud and clear, and Armstrong confirmed, "It was like perfect!"

Apollo 11 was the third American manned spaceship to achieve orbit around the moon. It was the beginning of the culmination of the nation's $24 billion effort to put men on the moon this decade.

Perfect has been the by-word of the Apollo 11 flight since its blastoff from Cape Kennedy, Fla., at 9:32 a.m. EDT Wednesday.

Of the four midcourse corrections built into the flight, the crew found it necessary to make just one because the initial trajectory was so accurate.

Later Saturday another firing of the main engine was scheduled to trim the lunar orbit and compensate for the mysterious variations in the moon's gravitational pull.

As the spacecraft settled into its lunar orbit, Armstrong reported, "Apollo 11 is getting its first view of the landing approach.

"The pictures that were brought back by Apollo 10 gave us a very good preview of what to look for here. It looks very much like the pictures, but like the difference between watching a real football game and one on TV.

"There's no substitute for actually being here."

Although the Apollo 11 crew hasn't been known for its talkativeness, Armstrong started radioing back description even before the spaceship swung behind the moon and into lunar orbit.

As the spaceship made its approach, he told ground control, "The view of the moon that we've been having recently is really spectacular. It fills about three quarters of the watch window, and, of course, we can see the entire circumference even though part of it is in complete shadow and part of it is in earthshine.

"It's a view worth the price of the trip."

After trimming their lunar orbit, the astronauts' next major maneuver will come at 1:38 p.m. EDT Sunday when Armstrong and Aldrin undock the spidery lunar lander from the command module to begin their descent to the moon.

They will travel in the same orbit as the command module for about two thirds of an orbit, then fire their descent engine, which will lower them into an orbit about 50,000 feet above the crater-pocked lunar surface.

At this point, shortly after 3:05 p.m. EDT, they will be rocketing along face down and backward at about 3,740 m.p.h. A second burn on their descent engine will begin braking their speed and aiming them toward a soft touchdown on the desert-like Sea of Tranquility, which, from earth, appears as a vast dark area in the right portion of the moon's face.

At an altitude of 500 feet, within 2,000 feet of their destination, the astronauts will start dropping almost vertically and will begin hovering to select a touchdown spot. They will also have tilted their spacecraft almost upright, with its windows forward to get a good look at their target.

Until they reach the 500-foot level, spacecraft computers - fed by radar and other sensing devices - likely will control most of the flight, but in the last moments Armstrong is expected to take manual control of the throttle and ease the spacecraft to a landing, much as he would a helicopter.

Should anything go wrong at any point he could punch on of the yellow and black abort buttons and shoot the landing module back aloft for rendezvous with the command ship.

Once Armstrong and Aldrin are on the lunar surface, however, Collins has no way of rescuing his colleagues.

Armstrong exuded confidence in the seemingly frail lunar lander Friday when he and Aldrin climbed into it to give it a preliminary check. Before a worldwide television audience, he joked he was going to tape shut the abort panel.

Five feet above the moon, probes on three of the lunar lander's four legs will touch the surface, flashing on a light and telling Armstrong to turn off the descent engine.

The touchdown itself will be at a speed of about 2 miles an hour. And - if all goes as scheduled - will come at 4:14 p.m., EDT, Sunday.

The moon walk itself could come anytime after the landing, depending upon what Armstrong decides. The original plan was to give the astronauts about 10 hours' rest on the lunar surface before letting them begin the arduous moon walk in their heavy moon suits - a task which has been likened to walking around in a deep-sea divers suit.

This plan was devised however, before officials knew how well the Apollo 11 crew would sleep on its outward voyage, and before Armstrong confessed that he probably would be too keyed up to sleep on the surface on the moon, in any event.

Whenever he decides to take the step, Armstrong will open the hatch of the lunar module and begin backing slowly down a nine-rung aluminum ladder. On the second rung, he will pull a ring out about 3 inches with his left hand, opening a door to an equipment storage area where a television camera is stowed.

The camera, mounted and prefocused, peeks out through a hole in a thermal blanket that protected it during the 250,000 mile journey from earth.

It is aimed at the bottom rung of the ladder to record that historic moment when Armstrong drops his booted left foot onto the lunar surface and takes man's first step into another world.

Earthlings will share the moment over one of the most intricate communications setups devised by man.