/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/34598299/450851146.0.jpg)

There's an important divide between Arab Sunnis and Shias in Iraq. The Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), a Sunni group, has grown powerful by exploiting Sunni discontent with Shia Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki's government.

But Iraq wasn't always this way; this level of violent conflict between Iraqi Sunnis and Shias is a very modern phenomenon. So what happened? Where did this conflict come from?

Fanar Haddad, a research fellow at the National University of Singapore's Middle East Institute, has some answers. Haddad is an expert on the history and politics of Iraqi sectarianism and the author of Sectarianism in Iraq: Antagonistic Visions of Unity. We spoke via Skype about how modern nationalism gave way to Iraq's present sectarianism and how the US invasion allowed low-boil tension to become something much worse. One crucial point he made is that Sunni identity, as it exists now, was not present in Iraq before the last decade. A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Zack Beauchamp: You're an expert on the Sunni-Shia sectarian divide in Iraq. Can you talk about how this divide became so deep, historically and politically? I don't buy the line that it's "ancient hatreds" reasserting themselves, but was this kind of violence inevitable after the US invasion in 2003?

Fanar Haddad: You're right not to buy the ancient hatreds line. The roots of sectarian conflict aren't that deep in Iraq. In early medieval Baghdad, there were sectarian clashes, but that is extremely different from what you have in the age of the nation state.

Come the 20th century and the nation state, we're all part of this new "Iraq" entity — you feel a sense of belonging, so it becomes a question of how you divide the national pie. And I think that's the main driver, the main animator behind sectarian competition in Iraq.

Soldiers in Iraq in 1934. Fox Photos/Getty Images

That's a very new one. The state was established in 1921. Not too long after that, you start hearing about how the majority — the Shias — are being neglected, excluded, marginalized, or what you have you. After that, you've got the ever-present Arab-Iranian or Iraqi-Iranian rivalry that superimposed itself (not entirely by accident) onto sectarian relations. For whatever political end, people will try to conflate or suggest Iran with Shias. This has been particularly divisive.

I'll skip through the next 80 years of statehood, except to say that throughout them, the default setting was coexistence. Sectarian identity for most of the 20th century was not particularly relevant in political terms. Obviously, this is something that ebbs and flows, but there were other frames of reference that were politically dominant. Come 2003, plenty changes.

ZB: How did things change in 2003?

FH: You can chart a course to 2003 from the mobilization of Shia parties in the mid-20th century, the Iranian Revolution [of 1979], the Iran-Iraq war [of the 1980s], the rebellion of 1991, 13 years of sanctions. These are all part of a cumulative process.

Iraqi students protesting and pledging their allegiance to the Baath Party, Iraq, 1963. Stan Meagher/Express/Getty Images

Come 2003, the main opposition forces against Saddam Hussein were ethno-sectarian parties. That's a really important point. Yes, we can blame — and we should blame — occupation forces and the promises that they pursued, particularly enshrining identity politics as the key marker of Iraqi politics. But that was something that these ethno-sectarian parties, the ones who were the main opposition force, advocated before 2003. This, to them, was the answer.

From a Sunni Arab perspective, the Shia parties and personalities that came to power weren't just politicians who happened to be Shia. They were politicians whose political outlook was firmly rooted in a Shia-centric, sect-centric view of things. I would say there were a number of prejudices, Sunni suspicions of the new regime. These were unfortunately validated by the nature of the new political elite, and their subsequent decisions and policies.

Post-2003 Iraq, I'd say identity politics have been the norm rather than an anomaly because they're part of the system by design. The first institution that was set up in 2003 under the auspices of the occupation was the Iraq Governing Council — which was explicitly based on sectarian apportionment. You know, 13 Shias, six Sunnis, or whatever it was, based on what were perceived as the correct demographics.

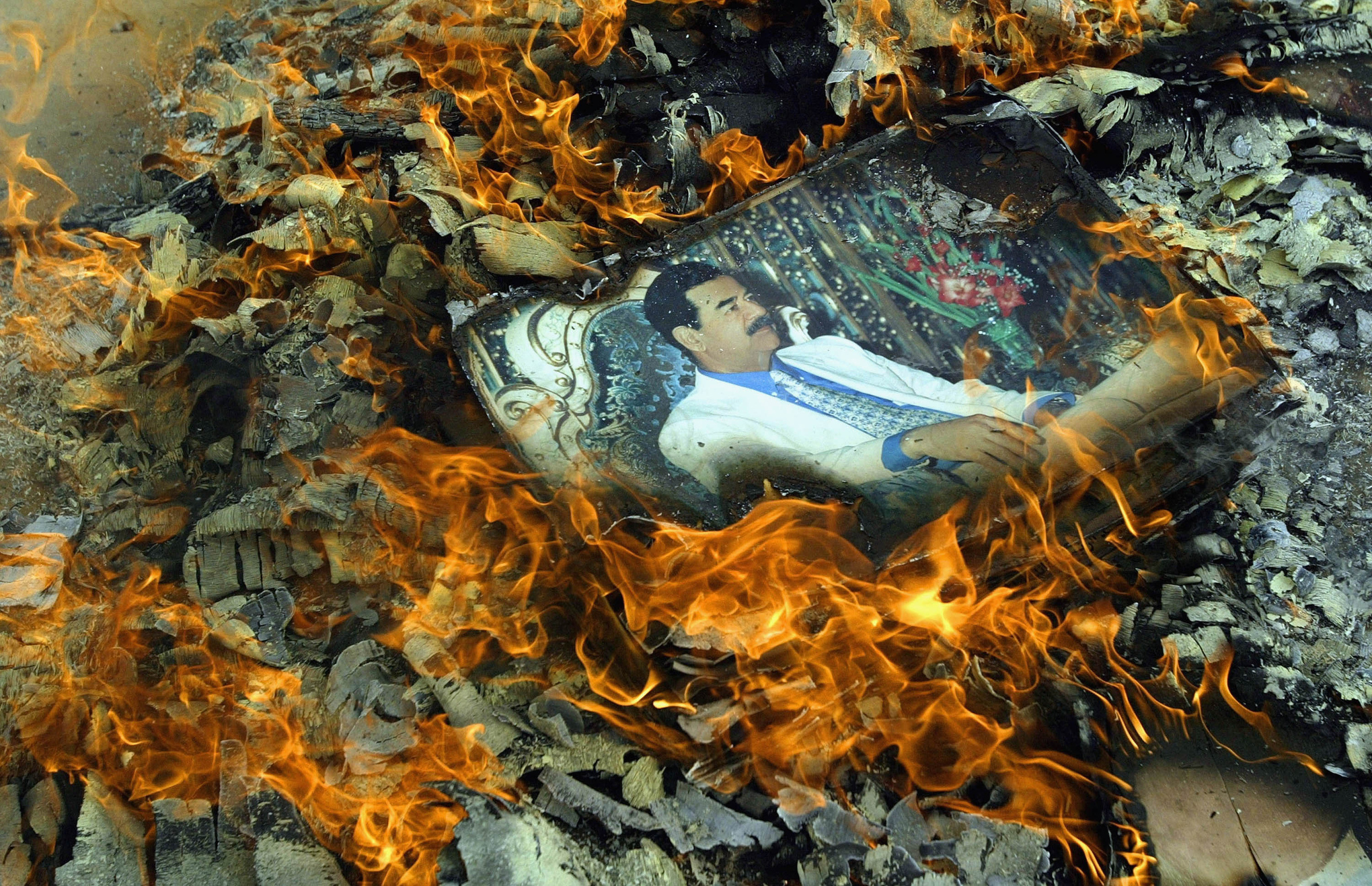

Picture of Saddam burns during the 2003 invasion. Chris Hondros/Getty Images

Not to muddy the water further, but we don't actually have anywhere near an accurate census for these things. They're just sort of received wisdom — that Sunnis are increasingly rejecting. The idea that they're a minority, that they're only 20 percent: this is something that Sunni voices since 2003 have been rejecting. Whether that's rational or not is not the point. The point is that they basically look at the demographic claims as Sunnis being marginalized and accorded second-class status on the basis of a lie. They do not accept that they are a minority, and this is a system that's based on ethno-sectarian demographics.

ZB: How do these sectarian divides affect people's view of the Iraqi state — not just the Maliki government, but the entire set of political institutions themselves?

FH: I'd say this point is crucial to pre- and post-2003 Iraq: the idea of the legitimacy of the state. It's also sort of crucial to what's going on now.

When 2003 came along, a lot of Shias and certainly a lot of Kurds welcomed it. They saw it as their deliverance as Shias and Kurds as much as it was the deliverance of Iraq. On the Sunni side, there was no such sentiment because there barely existed a sense of Sunni identity before 2003. It simply didn't exist in Iraq.

Now, what you see is the reverse. The Iraqi government is not popular with anyone, the popularity of the government is rock bottom, I'd say, but Shias are more likely to accord the state, the post-2003 order some level of legitimacy. Whereas there is a body of opinion of among Sunnis who just do not ascribe any legitimacy to it whatsoever.

That explains why, now, this rebellion is sweeping parts of Iraq. It's not all religious fanatics. There's a lot of people who place hope in this rebellion as a revolution, who see it as a nationalist movement. They see volunteering in the armed services as almost a sin, because they do not accord the Iraqi state any legitimacy whatsoever.

ZB: I thought that the point that you just made about Sunni identity not existing before 2003 was really fascinating. Can you explain what that means and how the invention of Iraqi Sunni identity came about?

The parallel we've always drawn with regards to Sunni identity is a parallel with race relations. There wasn't a coherent form of identity, like African-Americans or people in the UK from the [Indian] sub-continent or what have you.

The parallel that's being made is that Sunnis didn't see themselves as a having a perspective before 2003. It was not a Sunni view; it was the norm, the Iraqi view. [Zack here: this is sort of like the American notion of whiteness as the "normal" American view, a "default setting," or the "view from nowhere."]

Come 2003, it was a bit of a rude awakening. Because, for one thing, there was this abundance of previously curtailed or constrained expression. And a lot of it was sectarian expression. Nothing malicious, necessarily, but a lot Sunnis were completely oblivious to the deeply held Shia notions of identity they were just hearing about.

An Iranian boy holds a toy gun at an anti-ISIS protest. Atta Kenare/AFP/Getty Images

Again, the parallel with race relations is very obvious. Sunnis weren't concerned with or particularly knowledgeable about sectarian dynamics because it wasn't an issue for them. They did not perceive themselves to be on the losing end of sectarian dynamics, they weren't even aware of sectarian dynamics! So this is a game that they only started playing in 2003.

The other thing is that, in 2003, they had to form a Sunni identity whether they liked it or not because the system mandated it. The system required and made communal identity the central political marker. So they had to find that presentation along identity lines.

It's also reactive. You have this group, the Shias, that keeps banging on about the oppressed majority. There's the implication that you as a Sunni are kind of excluded from that. It's perfectly natural that they would form an identity along the lines that mirror the dynamic established in 2003.

And that has been accentuated over the past 11 years. Now you've got quite a strong sense of Sunni identity, one that has been anchored in a sense of victimhood. Perceptions regarding demographics play a role; as I said, they see themselves as being cheated into minority status. And yeah, victim identity at the hands of an overbearing, dictatorial Shia state — that's a very powerful feeling. It's got transnational echoes, which have helped accentuate this feeling of Sunni victimhood and identity.

ZB: So given this deep, emergent sectarian divide, is there any possibility that ISIS makes gains in Shia areas?

FH: No, I don't think so. A few towns might fall to ISIS forces and you hear about a massacre — that could happen. But in terms of taking Baghdad or going further south, I can't see that happening.

In terms of the pocket of Shia towns that are all over Iraq, it's possible that ISIS could take some of the ones [in largely Sunni areas]. But in terms of making gains in Shia areas, their ability is limited — otherwise, they would have taken Samarra by now.

ZB: Then there's the flip side of that question — how hard is it for the government and government aligned forces to make inroads into areas that ISIS controls?

FH: That is a harder question. Of course, it comes down to will they be able to take this territories? I don't think so, and for me, Fallujah is the benchmark. Seven months they've tried the city and couldn't take it.

Ahmad al-Rubaye/AFP/Getty Images

Now they've got vast swaths of territory that have fallen out of control. The government is going to have to have some allies on the ground — and they do. But it's not ISIS that's the bigger threat. The bigger threat are the other [Sunni rebel] groups. They have much deeper roots in these towns and cities. There are a lot of people who are sitting on the fence trying to see which way the wind blows. I'd say the immediate threat is more from non-ISIS groups.